What goes up should come down

Combining destratification with warm-air heating can result in significant energy savings for buildings with high roofs. Phil Brompton of Powrmatic discusses the design considerations

Thermal stratification is a phenomenon that will be very familiar to building-services engineers — as will its potential to waste energy in ‘shed’ type buildings if left unchecked. In fact the Carbon Trust has estimated that destratification in such buildings can reduce heating energy consumption by 20%.

In most buildings the occupied space only extends to around 2 m above the floor, so any heating of the air above this point is potentially wasteful. However, laws of physics dictate that warm air will rise to the highest point — the ceiling or roof space — and in doing so will push cooler air downwards into the occupied space.

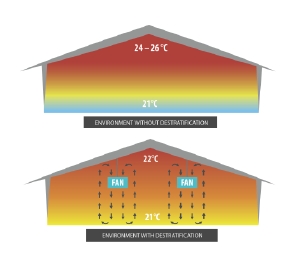

This can lead to a temperature difference between the occupied zone and the roof space of as much as 5 K (typical pitched roof building with an average height of 5 to 7 m). Clearly, such a temperature differential is indicative that a significant amount of the energy consumed by the heating plant is being wasted.

This situation also influences the rate of loss through the building fabric, because of the greater temperature difference between the air in the roof space and the outside air.

|

| Energy saver — Powrmatic’s CECx destratification fan. |

For example, if the set point temperature for the occupied space is 19°C and there is a 5 K temperature differential between it and the roof space, the air just below the roof will have a temperature of around 24°C. On a cold winter’s day, with an outdoor temperature of -1°C, there will be a temperature difference of 25 K.

In contrast, if the warm air is distributed evenly throughout the space at 19°C, the temperature differential between indoor and outside air is only 20 K, and the heat loss is lower than if there was no destratification.

This is a particularly important consideration in older buildings which may not have the same airtightness and thermal insulation levels that we would expect of more recent constructions.

Temperature gradients also have an impact on the natural rate of ventilation through leakage points in the building fabric — again most pronounced in older, ‘leaky’ buildings. Some of the warm, buoyant air rising into the roof space will leave the building through these leakage points, creating a small negative pressure that draws cold air into the building through lower-level leakage points. This ingress of cold air will reduce the temperature in the occupied zone so that more energy is consumed by the heating system to restore the set point.

The obvious solution is to return the warm air back to the occupied space using destratification fans in parallel with a warm air heating system. A well-designed destratification system will ensure there is only a very small temperature gradient between the occupied zone and roof space. In many cases this will make it possible to maintain the required temperature with fewer warm-air heaters, reducing capital and running costs.

In an industrial building where manufacturing or processing machinery generates heat, that heat will also be evenly distributed by the destratification fans, thereby reducing the load on the heating plant even further.

|

|

Energy efficiency and comfort are both enhanced in tall buildings by destratification. Temperatures shown are for a typical building |

A further benefit is that improved air distribution will minimise hot and cold spots in the occupied zone. Destratification fans can also be used without the heating to provide cooling flows of air in warm weather.

Whether they are retrofitted to existing buildings or a new building, destratification systems should always be designed by experienced professionals, taking account of a number of key design considerations.

There are essentially two types of commonly used destratification fan, so one critical consideration is selecting the most suitable fan for the project. Low-velocity blade or propeller fans work by churning the air, and these are most appropriate for ceiling heights between 5 and 10 m.

For spaces 10 to 20 m high, a high-velocity axial fan will be required to send a significant amount of air at high speed towards the floor.

Fan control is also important, and the controls should be configured to suit the requirements of space. Typical options include only operating fans when the heating is on, controlling the fans independently of the heating, linking fan operation to air temperature at ceiling height and controlling the speed of the fan to prevent draughts. There may also be a summer option for cooling.

It is obvious that a primary role of reducing energy consumption is to avoid wasting it. Using destratification fans in buildings that are prone to thermal stratification is therefore a cost-effective solution that will deliver a fast return on investment.

Phil Brompton is managing director of Powrmatic.