A considered approach to district heating

With many specifiers and contractors working on large-scale residential buildings yet to reap the benefits of large-scale heat networks, Pete Mills of Bosch Commercial and Industrial, explains the important role of CIBSE’s code of practice for heat networks to help the effective integration of boiler plant in a district-heating scheme.

The CIBSE CP1 code of practice for heat networks has become a terrific resource for the industry, especially those involved with the design of networks and energy centres. Its formulaic approach sets out the stages that should be followed to help reduce risks to the ultimate performance of a scheme. So how could this approach help designers when tackling specific elements such as the heat generators for the scheme?

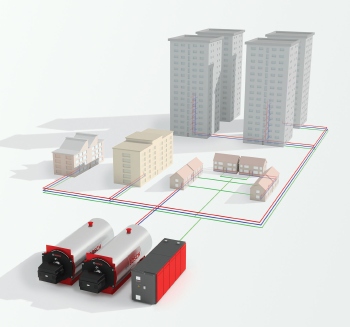

The key advantage of a heat network is that, once constructed, it can be agnostic of the fuel source used. This can help to future proof a scheme and open the possibility of using waste heat and renewable heat sources with back-up boilers. The combined scale of individual dwellings on a scheme makes renewable heat sources more practical to integrate and install.

Whatever source of heat is chosen as the lead heat generator, back-up boilers using fossil fuel will ensure security of heat supply and help to cope with peak-demand periods. These boilers will typically be chosen to ensure they can back up all the demand in the event of a failure with the lead heat source. With hundreds of homes on a single scheme, security of supply is a hugely important consideration that needs to be made from the outset.

The designer’s approach to heat networks must be quite different to that of normal building services, however. No longer is it acceptable to oversize key elements of the design. Reduction of network losses is critical as well as the efficiency and control of the heat producing and distributing plant.

So why have many schemes ended up with an oversized heat-generating plant that has contributed to poor network performance? It comes down to a lack of experience with heat networks and how the design should be approached.

A designer’s natural instincts are to allow some extra capacity in all elements of the design to compensate for errors or unknowns. But this approach can often lead to poor performance, increasing heat losses and reducing plant efficiency. The most basic of problems has tended to be the use of appropriate diversity for domestic hot water (DHW) demand, and this above all else has led to significant oversizing of a number of plants. CP1 addresses this problem and gives clear guidance to enable contractors to steer well clear of any potential pitfalls.

For small and medium heat networks, a boiler plant can be sized with reference to the thermal buffer storage used. The buffer storage is an essential component of a heat network; allowing sudden peaks from DHW demand to be accommodated as well as helping to ensure the lead heat generators are used as much as possible. The boilers can be sized to cope with the total heating demand plus enough capacity to re-heat the buffer vessel after a period of peak DHW demand. A reasonable timescale for reheating the buffer is one hour.

Once the total capacity of the boiler plant has been reached, it is important to consider that for most of the operation time the heat demand will be in the range of 10 to 25% of its peak. This means that a boiler plant should be chosen which can operate with a suitable turn down. Cascades of smaller boilers have a significant advantage here, since the turn-down ratio is based across the entire cascade. Multiple boilers also help increase the redundancy available for the plant overall.

CIBSE CP1 and AM12 (which advises on combined heat and power [CHP] for buildings) both recommend flow/return temperatures of 70/40°C for radiator-based systems to help reduce network heat losses. Working at the wider ∆T of 30 K using smaller pre-mixed gas boilers, for example, requires some thought to be given to the hydraulic design. Good, modern arrangements with individual boiler primary pumps and hydraulic separation will ensure flow rates are matched and low return temperatures are made use of via condensing boilers.

The integration of the boiler plant in relation to the lead heat generators is another area in need of careful consideration. There are many tried-and-tested hydraulic arrangements that accommodate renewable or CHP heat sources effectively; each design must consider the requirements of the heat source involved and how it will work to best efficiency. Control is a key element if boiler capacity is not to swamp the system with heat and deny the lead heat generator the available thermal load.

There is no doubt that the key to successful design of heat networks and their associated plant lies in the detail. A systematic and holistic approach such as that set out in CP1, ensures that essential elements of the design such as boiler plant are fully considered.

Pete Mills is commercial technical operations manager at Bosch Commercial & Industrial.