Naturally does it

Wayne Aston expounds the benefits of natural ventilation for optimum indoor air quality.

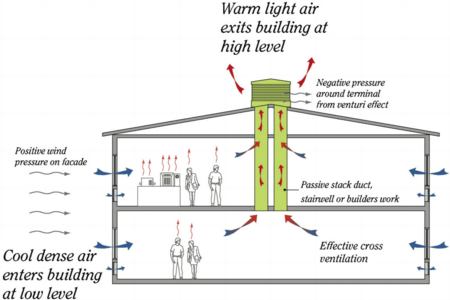

Indoor air quality has a huge and costly effect on commercial environments. According to the World Health Organisation, up to half of new buildings, or newly refurbished buildings, may cause Sick Building Syndrome (SBS). In worst cases, up to 85% of the building occupants can be affected — all the result of inadequate indoor air quality. The adage ‘build tight, ventilate right’ is therefore as true as ever. There must be sufficient flow of fresh air into a building and efficient removal of the ‘used’ internal air to maintain a healthy internal environment.

Naturally ventilated buildings are proven to reduce incidence of SBS, creating an appropriate flow of fresh air in and removal of the ‘used’, moisture- and carbon-dioxide laden internal air, with no noisy extraction fans. When we feel uncomfortably hot, cold or tired indoors, we open or close a window — the core principle of natural ventilation! The fact that the Department for Children Schools & Families prefers natural ventilation over mechanical alternatives in its Building Bulletin 101 Ventilation of School Buildings reinforces the effectiveness of the strategy, in its delivery of good indoor air quality, improved energy savings and 10 to 15% construction cost savings over mechanical systems — and best value over the life of the building.

Natural ventilation is not just better for our health, it is also better for the environment and bank balance too. Naturally ventilated buildings typically use less than half the energy of air-conditioned buildings. They thus have a significant positive impact on a building’s carbon emissions and also reduce capital costs by 15%. As a result, it is an acceptable tool to achieve BREEAM ratings of at least ‘very good’, under both health and energy categories. Further, maintenance can be substantially reduced over mechanical-ventilation or air-conditioning systems, as there are fewer moving parts to require servicing or replacement.

Natural ventilation is the oldest form of airing a building, but advances in technology now allow finite control — instead of the historic, very gratuitous approach. To optimise the efficiency of any ventilation system, it is best integrated at the building design stage, taking into account the building’s location and orientation and the geography of the surroundings. Other factors include its height above sea level, exposure and position of the Sun. Surrounding activity (whether a very rural, urbanized or industrialised area) affects external air quality, movement and temperature and, therefore, the air quality, movement and warmth within.

Software such as AirSoft, Airscoop Builder, which we have developed in conjunction with Environmental Design Solutions Ltd (EDSL) to interface with its TAS program, and our thermal modelling facility via De Montfort University’s Institute of Energy & Sustainable Development (IESD) can play a vital role in ensuring the proposed system delivers the continuous quality of air.

Such advances, coupled with state-of-art ‘intelligent’ control systems, enable finite control of the ventilation to minutely adjust the louvres of just one natural ventilator, or zone, through to whole buildings to optimise air quality and temperature in relation to changing activities within and climate without — whatever the season. The ventilators can be adjusted using a range of inputs ranging from internal and external temperature, internal CO2, humidity, air quality, rain sensors, wind speed and wind direction, and local timed over-ride controls. These sensory inputs are used to calculate the required ventilation flow rates for each zone, and the ventilators are adjusted accordingly. Yet the whole system uses minimal energy — requiring power only to attenuate the louvres as much or as little as required.

The key is to enable fresh air to move through the building, without draughts, dust and noise, and effectively remove the ‘used’ air. As natural ventilation works 24/7, using natural air movement, it not only ventilates the building when occupied during the day but also provides free night-time cooling. To remove heat gains that were built up during the preceding day. Allowing cool night air to flow through the building removes heat and cools the fabric, furniture and fittings — which in turn provides a cooling effect the following day. A natural night-time cooling strategy typically reduces the following day’s peak internal temperatures by 2 to 3 K and can reduce energy use for cooling by up to 80%.

Natural ventilation can also be combined with mechanical cooling to create a mixed-mode cooling strategy. This system is useful where there are high heat gain spaces such as IT suites, fitness rooms, retail areas or some modern offices. Studies show that 49% energy savings can be achieved compared to a mechanical-cooling and heat-recovery strategy, with a 50% reduction in maintenance costs — all adding up to on-going cost savings. This type of mixed mode approach can also provide an A-rated Energy Performance Certificate.

Because the strategy uses natural air movement, there are no noisy fans needed to circulate the air within, helping create a more peaceful environment, whilst still achieving effective penetration of the fresh air throughout the internal space. Any noise pollution can be further reduced by simple location of inlets above suspended ceilings, or even specification of additional acoustic attenuation to the unit — for example if the building is next to a busy road, railway or airport.

The developments and control mechanisms are all in place to enable good indoor air quality to be sustained — with benefits not only to the occupants but also the builder developer, owner and the planet.

Wayne Aston is technical director with Passivent.