Light at the end of the tunnel

The Department of Communities & Local Government (DCLG) recently published its consultation document outlining changes to the Building Regulations, which Alastair Ramsay believes provides grounds for real optimism on more effective lighting control.

In a recent issue of MBS (November 2011) Liz Peck of the Society of Light & Lighting argued that too much emphasis was being placed on lamps and luminaires to reduce lighting energy consumption and that a seachange in thinking was needed before proper progress could be made by embracing of better controls.

Today, we are sitting on a consultation document that, should it survive in its current format, delivers real optimism in four key areas.

First, as the energy/carbon limit targets for buildings are being further reduced, lighting energy measures will have to come to the fore. The reason is that the measures that have been used traditionally, such as glazing, insulation and biomass boilers, are very much operating at their optimum levels and so will simply not be able to deliver the additional energy reduction.

Second, the guidance notes now offer far better advice on the benefits of lighting control, and are weighed more in favour of it over purely manual switching.

There is also more emphasis on dimming, particularly for maintaining illuminance. This is aimed at eliminating the energy wasted by specifying initial lighting levels above those required — a common practice to offset the expected decline in light-source performance over time.

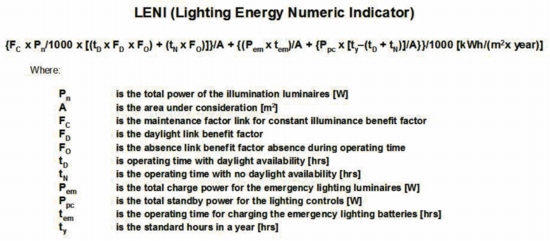

Finally, the full and proper introduction of LENI (Lighting Energy Numeric Indicator) as an alternative way of accounting for lighting energy use will give a more realistic method for lighting designers to use. And what’s more it’s a methodology that lighting designers and specifiers are already familiar with.

|

| Smart style — Arteor controls from Legrand are based on the Zigbee high-level communications protocol. |

In my opinion LENI will undoubtedly play the most important role in delivering significant energy savings from lighting — most notably as a means of ensuring designers can deliver good quality lighting which is fit for purpose, something that to date has proved extremely difficult to achieve within the SBEM modelling methods.

SBEM is designed to model a whole typical building but does not fully reflect the true benefits derived from installing lighting controls, an issue that was highlighted in the recent consultation documentation on the Green Deal.

The consultation document for the Green Deal and Energy Company Obligation (November 2011) stated: ‘Our concern is that, even with the improvements to the SBEM methodology we are putting in place, the Green Deal Assessment will not be equipped to consider in detail how a whole system (e.g. a lighting control system) might be designed in a non-domestic property to maximise savings. It would therefore be likely to lead to routine underestimation of the level of savings that could actually be made.’

Additionally, the fact that SBEM assumes presence and lux controls in its modelling of the target building, plus the presence of automatic dimming controls in daylit areas, is not well known and has resulted in lighting controls not being routinely adopted into buildings.

The result is that even simple levels of lighting control are often omitted, even in new-build projects, as a result of value engineering. This situation has been accentuated by the ease with which more static measures, such as insulation, have been implemented instead.

In contrast, LENI is fully focused on lighting. EN15193 specifies the way in which it is calculated. While the formula appears complex, when broken into its individual parts it is relatively easy to appreciate.

|

| Sensing a change — lighting control sensors may not be at the cutting edge, but they deliver vital energy savings. |

The various parameters, including occupancy patterns and target lighting levels for the spaces being considered, are entered, and the final calculation generates an energy use per square metre per year. For regulatory purposes, and as proposed in the Part L consultation, this calculated energy use is compared against a table giving a maximum target based on planned occupancy rates and target lighting levels.

In practice, specifiers and designers will rarely be faced with the complete formula as they will use lighting-design software that incorporates the LENI calculation — meaning the task is even more straightforward.

The proposals outlined in the Part L consultation do not guarantee the uptake of lighting controls in new buildings, but the increased prominence given to LENI and the improved guidance in the Compliance Guide will certainly play a major role in encouraging a far greater uptake in use.

Further, introducing these elements into the calculations of the Green Deal’s Golden Rule will give a kick start to tackling the hugely inefficient lighting schemes in existing buildings.

Whatever the final content of Part L, it does feel like we are making progress and that the gap between the type of lighting technology most designers talk passionately about and the type of technology being installed and used in buildings across the country will begin to vanish.

Alastair Ramsay is sustainable development manager for Legrand.