Warming to natural ventilation

One of the challenges of natural ventilation is reducing the expense of tempering cold draughts in winter. Shaun Fitzgerald of Breathing Buildings takes up the subject.

Why do many new buildings fail to provide good levels of air quality? We know that buildings comprised of rooms which have good access to the exterior façade or roof in quiet locations can be ventilated using manually opening windows or roof lights. Where buildings are in noisy locations or where there isn’t readily available access to the exterior, mechanical ventilation can be used. So, what’s the problem?

Mechanical ventilation uses fans to drive the air in and out of the building. To improve air quality, the flow rates need to be higher, and this in turn means the ventilation equipment needs to be bigger and more expensive, and more fan power will be required in use.

Natural ventilation is an attractive option for providing great air-quality levels. In fact, the concept of opening up the building to the outside when it is really nice provides stimulation and leads to greater occupant satisfaction.

However, there are significant challenges when it is cold and windy, or when it is hot.

Summertime overheating can usually be prevented by ensuring that the openings are sufficiently large.

However, the challenges of winter have not been properly tackled until fairly recently. The problems of cold conditions have historically been addressed in two ways.

• Subjecting occupants to cold draughts.

• Overcoming the draughts by pre-heating the incoming fresh air.

When occupants are subjected to cold draughts, the net result is that the dampers and windows are left closed. Even if an automated natural-ventilation system tries to open them, people simply isolate the system because they won’t put up with cold draughts.

Providing thermal comfort is a prerequisite for a ventilation system. The pre-heating option has therefore been widely used for many years by designers. Unfortunately this type of system is incredibly wasteful in terms of energy use.

If people experience draughts when the air which reaches them is below 16°C, then when the outside temperature falls below this level the heaters are needed. However, there are now so many internal gains in most buildings from people, IT, lights etc. that the building itself doesn’t need heating until the outside temperature is somewhere between 0 to 5°C. The difference between turning on the heating system when the outside temperature falls below 5°C and 16°C is enormous!

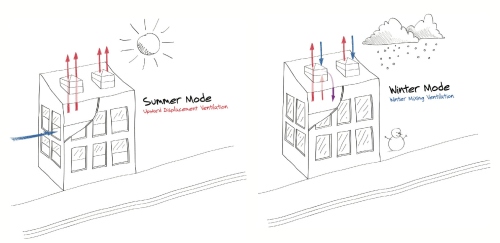

|

| Natural ventilation in summer and winter. Heat recovery in the winter prevents the problem of cold draughts with out having to turn on the heating system when the external temperature falls below 16°C |

The UK is a relatively temperate climate, and the temperature on most days in the winter is between 5 and 16°C. In other words, we have been using heating systems for more than half of the winter to cure cold draughts when the buildings didn’t actually need heating!

Recent innovations in natural ventilation have focused on pre-mixing cold fresh air and warm room air to mitigate the cold draughts. This simple concept literally halves the heating bills of a building.

The type of system needed to deliver a pre-mixed air stream to a room varies with the type of building.

Where a room has easy roof access, there is merit in providing the mixed air via the roof in winter.

Where a room does not have roof access but does have access to an atrium, the atrium itself can be used to naturally mix incoming cold air in winter with the building air.

Finally, where a room just has access to the façade, then a façade-based natural-ventilation system with a mixing device can be used.

The innovative natural ventilation products from Breathing Buildings can be used in both new buildings and refurbishments. There are over a hundred buildings now up and running with the e-stack natural ventilation system.

With the refurbishment of the Swan Theatre in Worcester having involved replacing the entire roof it was straightforward to include roof stacks in the design.

The atrium-based system can be applied to refurbishment projects where there is an atrium.

|

| The bulkhead unit at the right of this photo of Stratton School provides natural ventilation with heat recovery. |

However, the façade based system offers the biggest opportunity for the refurbishment market.

Existing buildings provide the biggest challenge and, hence, opportunity for reduction in energy use in the UK. The façade based system can be readily mounted in a bulkhead either above or adjacent to a perimeter window. Examples of the façade system already deployed in buildings include Wembrook and Stratton Schools.

The potential for energy savings is not just theoretical. Heating bills from installations have been closely monitored, and the savings are in line with predictions. Furthermore, we have verified that the air quality levels in these buildings are above and beyond the requirements of current guides. The levels of CO2 recorded at Queen Alexandra College in Birmingham over a week are typically below 1000 ppm, which is well below the daily average requirement for schools of 1500 ppm.

It is clear that the system is able to provide vastly superior levels of indoor air quality, but without the penalty of cold draughts or heinously high heating bills.

Shaun Fitzgerald is managing director of Breathing Buildings.