Moving forward without fossil fuels

As methods of heating buildings and processes evolve to reduce carbon emissions, the boiler still has an important role to play, though this too is evolving, says Ian Dagley of Hoval

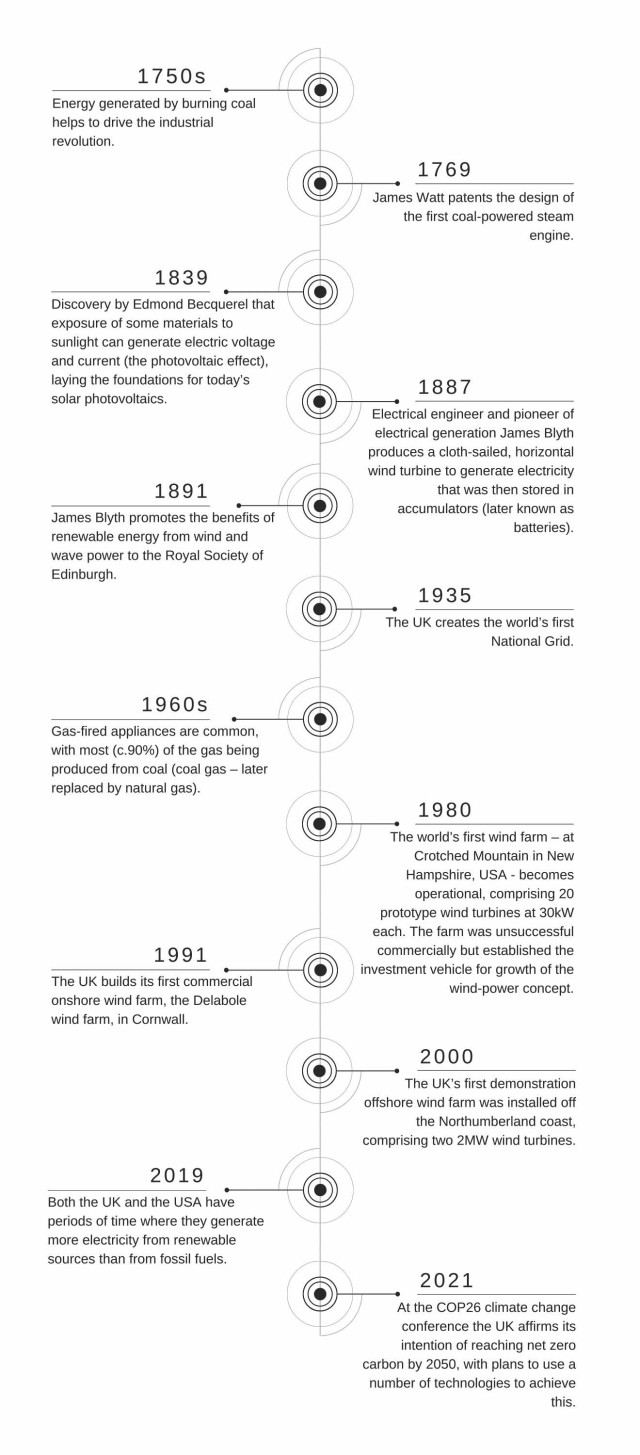

Recent events in the UK and beyond have made it clear to all but the most sceptical that climate change is real and there is a need to accelerate the phase out of fossil fuels. This is particularly true for heating buildings and industrial processes, and in transportation.

To that end, the UK government has frequently re-affirmed its commitment to achieve net zero carbon by 2050 – something that can only be delivered through a massive reduction in our use of fossil fuels. In this respect, the fossil fuels used for space heating, domestic hot water (DHW) and process heating have all come under scrutiny.

To replace these fossil fuels there needs to be a programme of change that replaces combustion wherever possible and - in the many areas where this isn’t currently feasible - introduce alternative fuels for combustion. These approaches need to be deployed alongside each other, using a ‘horses for courses’ approach.

These horses will need to be set running quite quickly as the government has signalled its intention to use the Building Regulations to phase out fossil fuel heating. For example, from 2025 new homes will not be able to achieve new reduction targets if they use a gas boiler, so alternatives will be required.

A pragmatic approach

In determining which horse is the best bet for each situation we need a pragmatic approach that leverages the pros and cons of each technology. For instance, the growth in generation capacity of renewable electricity has led some to suggest, even at government level, that heat pumps could replace traditional boilers for heating and hot water. As a company that designs and manufactures both boilers and heat pumps, we can certainly see considerable scope for the latter, but there are also issues that will limit the breadth and speed of their application.

In particular, heat pumps can only operate efficiently at lower water temperatures than boilers. This is because the condenser operating temperature is largely a function of the pressure that the refrigerant can be elevated to. This sets its dew point and in most heat pumps this is simply not high enough to lift the system heating water to the same level of temperatures as can be achieved by a conventional combustion-based boiler. Heat pumps therefore generally must operate with a lower maximum heating system flow temperature.

This means existing radiators and other heat emitters will not emit as much heat when served by a heat pump, making it difficult to introduce heat pumps as the sole heat source for space heating to many existing buildings without considerable investment in improved thermal insulation. It has also been estimated that between 600,000 and 1 million homes would require upgrades to their electrical network to make them suitable for running heat pumps.

Other concerns that have been voiced include issues with maintaining high enough DHW temperatures to meet anti-Legionella requirements the Global Warming Potential of the refrigerants used in heat pumps.

It is worth noting that, in industrial, logistic and ‘shed’ style retail premises, heat pumps can be incorporated into ventilation systems to provide highly efficient space heating and cooling.

Moreover, heat pumps in general – and air source heat pumps in particular – undoubtedly have a key role to play in the UK’s net zero carbon transition and the UK government is targeting installation of one million heat pumps a year by 2035.

Minimising combustion emissions

For all of the reasons above, there are many commercial, industrial and residential applications where combustion is the only way to generate the required amount of heat. Therefore, there are very good reasons for putting as much effort into finding alternative fuels as has been devoted to building the renewable energy infrastructure.

Currently, the most talked-about fossil fuel alternative for combustion is hydrogen. Indeed, it was the second point in the Prime Minister’s 10-point plan for achieving net zero carbon and the government has announced significant funding to support research into this area. Anticipating this, Hoval’s UltraGas 2 boilers are now ‘hydrogen-ready’ and can be easily switched from natural gas to hydrogen when the time is right.

Hydrogen is an attractive alternative to gas because the waste product of burning hydrogen is water, rather than the emissions associated with gas combustion. The challenge is to ensure that the hydrogen is produced without emissions.

The preferred production method is to split water into hydrogen and oxygen using electricity from renewable sources (so-called green hydrogen) as this method has zero net emissions. However, with a parallel push for heat pumps and electric cars, there is going to be considerable pressure on the capacity of the renewable electricity infrastructure.

Another option is to bring natural gas and steam together to release both hydrogen and carbon dioxide (blue hydrogen). With carbon dioxide as a waste product, this must be used in conjunction with carbon capture and storage to avoid emission of greenhouse gases. Also, of course, the steam will need to be generated by heating water so there is a balance to be achieved here.

The current timetable for introducing hydrogen is to begin blending it into the mains gas supply by 2023 and, by 2030, most of industry will be expected to have switched to either a blended fuel or have fully switched from natural gas.

HVO

Whilst gas is the dominant fossil fuel used for heating, there is also a significant amount of oil-fired heating equipment in use. A promising replacement is Hydrotreated Vegetable Oil (HVO), derived from used cooking oils and waste fats. Recent research has shown this to be a direct drop-in for gas oil in larger heating appliances and a near drop-in for kerosene in residential installations.

Summary

For all of the reasons discussed here, there are many obstacles to overcome in the path to net zero carbon. To meet these challenges, we need to be looking at how we make use of the most appropriate technologies for each project, potentially using sophisticated control to optimise performance across a mixed heating system that integrates several technologies.

Building services engineers have played a pivotal role in the progress that has already been made in reducing carbon emissions. They will continue to do so by working closely with manufacturers to apply the various technologies available in the most efficient manner.

Ian Dagley is General Manager at Hoval