The bridge to a lower-carbon future

With the introduction of the new Renewable Heat Incentive (RHI) for domestic properties and a revised scheme for commercial properties, Mike Malina looks at the prospects for this industry sector.

Energy prices are only likely to go one way in the coming years — up. This is evident by the price trends of the last few years as we face diminishing supplies of fossil fuels, made more volatile by political events around the world’s major geographical areas where these sources are concentrated. The Middle East and Ukraine are recent examples. This is likely to make lower-carbon and renewable heat increasingly attractive and financially sensible as it gives us more energy-supply security.

This raises the prospect for not only prioritising using less energy in the first place by insulating and making buildings more airtight and also ensuring that building-engineering-services systems are well controlled and above all well commissioned and maintained. When this process has been undertaken, we can then look at producing heat more efficiently and, where possible, using lower-carbon technologies.

The prospect for the renewable and lower carbon technology market is looking a lot more favourable than a few years ago. The introduction of the domestic Renewable Heat Incentive (RHI) looks like providing a big opportunity for heating contractors and installers to improve their profitability and create more business opportunities.

At present heat is not getting the same profile and level of publicity as electrical generation. People can see solar photo-voltaic panels on the roof, but heating is hidden away. A higher profile for heat would help create this, and the expanded RHI scheme provides a good opportunity to get the message out to both the industry and the consumer.

We are certainly starting at a low base. Renewables account for just 1% of heating in the UK but more than 15% of electrical power generation — up from just 9% in 2011. We are indeed heading for around 20% renewable electrical generation by the end of the decade as the country tries to drastically reduce carbon emissions from coal-fired power stations.

The Government also wants to increase the proportion of total heating supplied by renewables to 12% by 2020, but with the slow start of the initial commercial RHI scheme which started two years ago it is unlikely to be achieved. Nevertheless, the extension of the scheme in April 2014 to cover the domestic market could certainly deliver a possible 5% proportion of renewable-heat supply, which would be a great step in the right direction. The reinvigorated RHI has been reinforced by improving the tariffs payable to some renewable heating technologies and extending the list of technologies eligible for support.

Key to the scheme’s implementation is the priority of making sure suitable installers are appropriately qualified. So investing in the right skills is vital, as well as checking and enforcing good design and installation. This will be essential to avoid cowboy installers who could hijack this growing domestic market and may deliver poor-quality installations and undermine the reputation of the whole renewable heating industry.

We must also be alert to the fact that even good-quality installers could fall into technical traps and make poor choices over renewable installations. An example which has happened at a number of housing associations is specifying a heat pump as a direct replacement for an gas- or oil-fired boiler. Installers needed to take a more detailed look at the whole system, including appropriately sized heating emitters as well as the integrity of the building fabric to take account of the lower flow temperatures from heat pumps, maximising their seasonal efficiency. Ultimately, Installers have to be MCS equivalent (Microgeneration Certification Scheme) qualified and have to work to the specification PAS2030. The technologies themselves also have to be MCS certified.

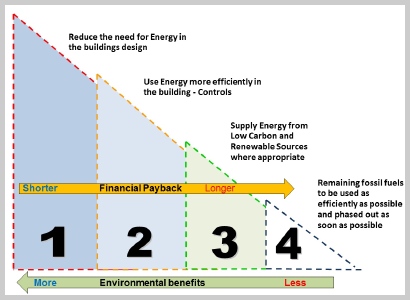

As an industry we must always employ the energy hierarchy, which prioritises energy saving and reduction measures before renewable technologies are considered. It makes good business sense to invest in energy efficiency as relatively low-cost measures that have a shorter payback. This will also improve the credibility and profitability of the contractor by delivering more savings for the customer.

The most likely market for RHI-funded projects is in rural locations off the main gas grid, where consumers are currently tied to using expensive oil and LPG heating. It is currently 50% more expensive to heat a building with oil and 100% more expensive with LPG than natural gas.

In the UK we have the potential for converting many of the four million off-grid properties to biomass or heat pumps, supplemented with solar thermal for hot water. This, in conjunction with improved insulation, could take the country very close to a good level of provision of heat from renewable and lower carbon technology.

The RHI commercial tariff is guaranteed for 20 years. With the domestic scheme the payments are compressed into seven years making it a particularly attractive proposition for consumers. It is possible to make £13 000 a year from a 100 kW biomass installation, according to the RHI operator Ofgem, which provides detailed payment estimates on its website.

I believe the RHI could be a major incentive for a bridge to a low-carbon future, as it represents the best opportunity to increase the proportion of total UK heating supplied by renewable and lower-carbon technologies.

Mike Malina is director of Energy Solutions Associates and the author of the book ‘Delivering sustainable buildings’ (which pulls no punches), published by Wiley-Blackwell. Readers of MBS can get a 20% discount using the code VBB09 at the link below.