Clean ductwork increases staff performance

Not only is there legislation covering the cleanliness of air-distribution systems, but poor indoor air quality can have a such an adverse effect on productivity that the cost of achieving it is very small. Craig Booth of System Hygienics explains.

A regular supply of fresh, clean air is essential for a safe, healthy and, moreover, productive working environment. However, it is something that is often taken for granted.

Building owners and facilities managers tend to hope that filters will ensure that duct systems remain clean and healthy, but of course no filter is absolute.

Even the highest-efficiency filter will let some particulates of some size through. What filters do change is the rate of fouling — from very slowly indeed downstream of a HEPA filter to rather quickly downstream of a simple pleated panel filter.

Of course good filtration efficiency depends on proper fitting without gaps or subsequent failure — which unfortunately cannot be taken as a given in every circumstance. Ultimately, a dirty system cannot supply clean air.

There is legislation covering the cleanliness of ductwork systems, primarily the Workplace Health, Safety and Welfare Regulations ACOP 52 which stipulates: ‘Mechanical ventilation systems (including air-conditioning systems) should be regularly and adequately cleaned. They should also be properly tested and maintained to ensure that they are kept clean and free from anything which may contaminate the air.’

Two publications provide more information on how to achieve clean systems and how to measure their cleanliness. One is BS EN15780: ‘Ventilation for buildings — ductwork — cleanliness of ventilation systems’. The other is the Building & Engineering Services Association’s ‘Guide to Good Practice TR19 (2nd ed. 2013) ‘Internal Cleanliness of Ventilation Systems’

|

| Fig. 1: With staff costs dominating the typical operating costs of a business, spending a small amount extra to improve productivity is extremely cost effective. (With thanks to World Green Building Council) |

You might hope that simple good housekeeping and common sense would be obvious enough, but most employers want to see some bottom-line benefit to justify expenditure on their buildings and property.

As building-services professionals, we visit a lot of buildings and tend to develop a ‘nose’ for dirty, poorly-maintained and inefficient buildings, where both the fabric and the occupants of the building feel tired.

The effects of poor indoor air quality tend to be low-level but chronic, rather than acute and life-threatening. The Health & Safety guidance note (HSG 132) ‘How to deal with sick building syndrome: a guide for employers, building owners and building managers’ makes the point that while the symptoms may be relatively mild, they are not trivial to those suffering the effects and that they cause significant costs to businesses through:

• reduced staff efficiency;

• increased absenteeism and staff turnover;

• extended breaks and reduced overtime;

• lost time in dealing with complaints.

Professor Clements-Croome and Rachel Luck of Reading University’s School of Construction Management & Engineering and Reading Business School, respectively, produced an excellent paper: ‘Environmental quality and the productive workplace’. It describes how it is much more costly for businesses to employ people than it is to maintain and operate a building. Hence, spending money on improving the work environment is the most cost-effective way of improving productivity, because a small increase of 0.1 to 2.0% in productivity can have dramatic effects on the profitability of a company.

This last point was underlined by the World Green Building Council’s recent report ‘Health, wellbeing and productivity in offices’, which was funded by JLL, Lend Lease and Skanska. The relationship between cost changes to the various components of typical (office) business costs is neatly illustrated in Fig. 1.

Work such as that by Pawel Wargocki and Ole Fanger illustrates the adverse effect on productivity of poor air quality. They used proof-reading as a test of concentration and accuracy and could show a straight-line relationship between performance and indoor air quality rating. In a world where human job performance is increasingly mental, or ‘intellectual’, whether by a junior clerk or a senior fee-earner, the effect of even small variations in an employee’s sense of comfort and wellbeing can have large effects on their output. Indeed, we’ve probably all experienced at some time in our lives the ‘just-can’t-get-started’ feeling.

|

| Fig. 2: Poor indoor air quality has an adverse effect on productivity — with thanks to Pawel Wargocki, Technical University of Denmark. |

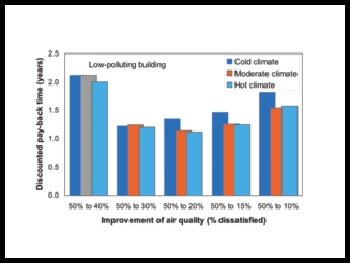

In a paper for the Berlin Conference on ‘Enhanced building operations 2008’ the researchers presented the results of field studies and laboratory simulation, which showed that the payback on improved indoor air quality can be very attractive. The paybacks (Fig. 2) are based on balancing the increased energy and maintenance cost against productivity improvements. They make no account of any reduced health or absenteeism costs.

It is still probably true that where the USA leads, Great Britain will follow, and open-ended legal liability on the part of property owners and employers continues to grow throughout the developed world. Erin Grossi of Underwriters Laboratory in a paper entitled ‘The dawn of the building performance era’ for the Toronto ‘Green real estate conference’ describes poor indoor air quality as a ‘sleeper issue’ and cites 14 000 pending toxic-mould lawsuits as evidence of the need for careful maintenance management.

In many ways, the simpler argument to make for cost saving relates to the energy cost of pushing air through dirty systems, especially at restrictions such as the AHU heating or cooling coils. A landmark study was carried out for ASHRAE which was able to compare one of four vertical zones of a 34-storey building in Times Square, New York City. The nature of the plant and zoning meant that accurate assessment could be made of energy ‘not used’ after cleaning the zone’s central AHU coils. The measured saving amounted to the equivalent of £26 000. Besides the ‘hard-cost’ results, there were significant ‘soft’ benefits. The engineers reported: ‘Overall tenant satisfaction with the building environment has been improved as evidenced by the property manager’s communications and positive feedback.’

Craig Booth is technical sales manager with System Hygienics.