Do you have an HCFC plan?

The ban on the use and sale of virgin HCFCs in refrigeration and air-conditioning systems has been in force in the UK for 18 months, yet many operators continue to rely on the availability of reclaimed or recycled HCFCs for their servicing and maintenance purposes. Mark Hughes explains the risks associated with this approach and provides an evaluation of options for facility managers to ensure business continuity.

The Montreal Protocol marked the beginning of the end for the use of ozone-depleting substances such as CFCs and HCFCs around the world. The most harmful ozone-depleting substances (such as CFCs like R12 and R13) were banned in the 1990s.

In Europe, the EU Regulation 2037/2000 (now replaced by 1005/ 2009) banned the use of less-harmful ‘transitional’ HCFCs (predominantly R22) in new refrigeration and air-conditioning (RAC) systems from 2000 onwards.

Most recently, 1 January 2010 saw the extension of the ban to include the use of virgin HCFCs for the maintenance or servicing of existing RAC installations. From 2015 it will become illegal to use any HCFCs to service RAC equipment, making the use of recycled or reclaimed HCFC illegal as of that date.

These ongoing steps towards the complete phase-out of HCFCs represent a very real business threat to any company using a refrigerant such as R22 for its cooling or air-conditioning systems. Those sectors at greatest risk include the food and drink industry, petro-chemicals, pharmaceuticals, health, retail, hospitality, finance and data-processing. Typical examples include refrigeration systems in supermarkets, blast chillers, cold stores, process coolers and many types of air conditioning in buildings as well as in transport refrigeration.

Whilst it currently remains perfectly legal to use existing RAC equipment containing R22, the operators of such systems must rely on the availability of reclaimed and recycled R22 for servicing and maintenance. The dangers of this approach are not only the risk of future shortages — a number of suppliers of reclaimed R22 state that the majority of the material they have is reserved for existing customers, which leaves little left over for the rest — but also an increase in cost due to its scarcity of supply. Over the course of the last 18 months, for instance, the cost of R22 in the UK has risen by a factor of 10.

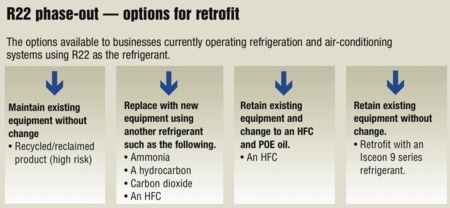

The risks associated with maintaining RAC systems based on reclaimed or recycled R22 mean that alternative phase-out solutions should be considered.

The first option would be to look at new equipment that runs on alternative refrigerants such as ammonia, hydrocarbons, carbon dioxide or hydrofluorocarbon (HFC) refrigerants such as Suva from DuPont. Whilst this is an expensive option, incurring downtimes ranging from days up to several weeks, it would perhaps be the most sensible and cost-effective option if the current system is nearing the end of its life.

The second alternative is to keep the existing equipment running, and to modify it for operation with HFCs such as R404A or R407C). Such a conversion requires a change to polyester oil and some further technical modifications. The downtime would be measured in days because of the need to completely remove the existing mineral oil.

Finally, the third and often most efficient option in terms of cost and time, is to use a retrofit HFC blend refrigerant that requires only minimal technical modification of the existing RAC system and downtimes of half a day to a day when carried out by experienced and suitably-trained contractors. An example of HFC blends is DuPont’s Isceon range, which has become a widely accepted retrofit option for systems that are working well.

That is the experience of JCB Finance Ltd., which converted its existing air-conditioning systems at its head-office in Rochester in Staffordshire, to Isceon MO29 (R422D). By so doing, the company not only avoided any future potential shortages of reclaimed R22 but also saved itself the cost of replacing its current, well maintained equipment with new systems. The conversion was carried out by air-conditioning contractor Temperature Control Ltd and caused no interruption to the provision of air conditioning to the offices. It also required very few technical changes.

Ultimately the best phase-out solution will need to be determined on an individual basis and will fall within one of the afore-mentioned options, depending on criteria such as the age and condition of equipment and the company’s current requirements.

What is certain is that doing nothing is not a sustainable option and that timely action planned now could save significant disruption and cost in the future.

Mark Hughes is the North European sales manager with refrigerants supplier DuPont.