Towards low-energy IAQ

Achieving good indoor air quality (IAQ) in buildings can be expensive in terms of energy consumption. David Black of Flakt Woods examines how that cost can be minimised.

Commercial buildings continue be subject to increasingly stringent legislation and planning criteria, all designed to meet the Government’s proposed target for zero-carbon buildings by 2019. Rightly so, the primary focus for building managers will therefore be to reduce CO2 emissions by improving energy efficiency.

A major part of this is improving air tightness, especially in new buildings. Although this is positive news for reducing heat loss and improving efficiency, it does mean that unless an effective indoor-air-quality system is implemented, the quantities of fresh, outside air being introduced into the building will be compromised.

Of course, energy efficiency is going to take the lead during the specification of HVAC plant. However, it is essential for building managers to understand the impact poor IAQ can have on businesses and building occupants, and ensure that any new system will adequately ventilate the property.

Figures suggest that we spend more than 90% of our time indoors. Whilst there is a good understanding of outdoor air pollution, few people realise that indoor air can be as much as 50 times more polluted than outdoor air.

One of the main causes of poor IAQ in commercial buildings is pollutants called volatile organic compounds (VOCs), which are naturally emitted from a range of ordinary items, including furniture, carpets, paints, varnishes, cleaning products and even the building fabric and materials — especially when new.

Regular exposure to VOCs can irritate pre-existing conditions occupants may have, such as asthma and eczema, or cause rhinitis, dizziness, headaches, coughing and sneezing. Exposure to VOCs can also cause fatigue, affecting the concentration of employees.

The NHS now recognises how common symptoms, such as those caused by VOCs in the workplace, can be attributed to poor IAQ in the form of ‘sick building syndrome’ and signposts businesses to invest in better ventilation to help reduce symptoms(1).

The push for more airtight structures to boost the energy performance of buildings means the levels of VOCs in schools, offices and healthcare facilities continue to rise, but studies have also shown that because humans expel carbon dioxide, there can be a high concentration of this gas in densely occupied, confined areas such as offices. Regular exposure to such levels of CO2 can result in lethargy, sleepiness and reduced concentration — with an adverse effect on the productivity of employees.

Worryingly, statistics indicate half the British workforce have suffered headaches, tiredness and felt less productive because of stale air and stuffy working environments(2).

In terms of managing IAQ, the UK’s focus on energy efficiency and the reduction of carbon emissions means the use of natural ventilation has been largely encouraged in new buildings.

Natural ventilation is the supply and removal of air without the use of mechanical systems. It can be achieved by use of operable windows and trickle vents, or through the temperature and pressure differences between spaces — known as the ‘stack effect’.

However, while these methods use very little energy and can possibly be incorporated into the design of new commercial buildings, it would be nearly impossible to modify an existing building in this way — and extremely expensive to do so if it were in fact possible. It’s also worth considering that, to achieve adequate levels of ventilation, windows may need to be opened wide for long periods of time, creating additional noise pollution and security issues.

Although natural ventilation may be the right option for appropriately designed new-build projects, refurbishment projects and some new buildings will require different thinking. Energy-recovery units (ERUs), sometimes MVHR (mechanical ventilation with heat recovery) units are a proven solution for commercial premises where effective natural ventilation isn’t possible or where the manager of a building estate has employed a combined approach to meeting regulations and delivering acceptable IAQ.

ERUs work by extracting moist, stale air from inside the property and replacing it with fresh air from outside. The system then utilises the heat from the outgoing air to essentially warm the incoming air via an air-to-air heat exchanger mounted within the ERU.

Crucially, ERUs offer substantial energy-saving potential. By recovering thermal energy from the outgoing air, displacing fossil fuels predominantly used to generate heat for space heating, energy bills will of course be greatly reduced and it can also achieve substantial carbon reductions, especially for sites with multiple buildings.

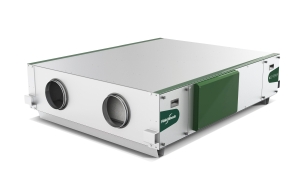

When ERUs such as Fläkt Woods eCO Premium range are incorporated into a building’s design and combined with other measures such as glazing upgrades, cavity wall insulation or heating system improvements, energy consumption and carbon reduction will see a notable improvement.

ERUs are designed to provide comfort and energy efficiency to a wide range of applications within the commercial sector, such as educational institutions, offices, healthcare facilities and retail outlets.

As well as being highly efficient and capable of recovering 85% of the thermal energy, the range also offers an unprecedented level of control and intelligence. Efficiency can be further boosted using sensors that can automatically adjust to changing demands within a room, offering demand-controlled ventilation.

A presence detector can also be specified to switch the system on when the room is occupied and off again when it is empty. A CO2 sensor can also adjust the supply of fresh air proportionally to the number of people in the room at any time.

British Standard BS EN 13779 provides four classifications of indoor air quality that non-residential buildings such as schools, should aim to achieve. F7 supply filters, which result in 'moderate air quality,' are always fitted with the eCO Premium range. Other products on the market typically use G4 filters, which can only achieve air quality that is poorer than ‘low’.

Using energy-recovery mechanical ventilation could be a very cost-effective measure for building managers to consider when seeking refurbishment of existing systems; it most certainly should be specified from the outset for new builds if natural ventilation is not an option, or if a combined approach is taken.

Thanks to the latest innovations from leading manufacturers such as Fläkt Woods, the commercial sector now has access to a range of ventilation systems designed to combat the issue of IAQ, whilst also improving energy efficiency, meeting stringent regulations and cutting costs.

David Black is national product sales manager at Flakt Woods.

References

1: www.nhs.uk/conditions/sick-building-syndrome/Pages/Introduction.aspx

2: Research conducted by Populus for Guardian Air Hygiene; www.gwtltd.com