The road to wellbeing

In this month’s MBS round table discussion, sponsored by LG, our panel of experts considers the topic of wellbeing and the contribution of building services to the health and happiness of occupants at work and at home. By Karen Fletcher

If you think that ‘wellbeing’ is a word you’re hearing more often these days, then you’re right. It’s a topic that is finding an increasing amount of traction in certain sections of the property industry, and building services have a significant contribution to make to this area.

|

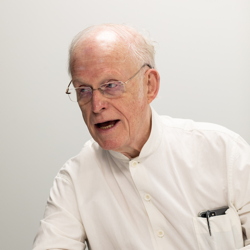

WHO’S ON THE PANEL? Professor Derek Clements-Croome - Reading University Jack Friend, Managing Director - Hasman and BESA member Jonathan Moore, Design Manager - Kane Group Building Services Andrew Robinson, Managing Director - Exi-Tite Dr Graeme Sherriff, Research Fellow & Associate Director - University of Salford Sustainable Housing & Urban Studies Unit (SHUSU) Andy Slater, Senior Engineering Manager, UK & Nordic - LG Air Conditioning and Energy Solutions |

Professor Derek Clements-Croome who, among other roles, is an advisor on occupant health and wellbeing to the British Council of Offices (BCO) says: “There have been many attempts to define wellbeing and they generally all point back to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs from 1943. It encompasses the physical, social and mental wellbeing of people. It’s not confined to one particular area.”

Dr Graeme Sherriff, associate director of University of Salford’s Sustainable Housing and Urban Studies Unit (SHUSU) agrees: “Wellbeing is a very broad concept and the research that we have been doing recently with social housing residents demonstrates that it has to have a broad definition relating to quality of life; it’s not simply a point between two temperatures, it’s much more complex than that.”

Clements-Croome is also clear on this point: “Wellbeing is not simply comfort. I see wellbeing in three layers. First you have comfort which is the basic health and safety level, for example a certain temperature, sound level and so on. Then we have an individualisation or personalisation layer. All our research shows that people like some level of control over their space. And thirdly we have the wow or sparkle layer which includes things such as the spaciousness, attractiveness, views out, greenery and diversity of the space. These three levels, together with management and job satisfaction, contribute significantly to wellbeing and help to achieve a flourishing environment for people to work and live in.”

|

|

Andrew Slater: “MEES is making landlords take action on energy efficiency through legislation. We need a similar standard on wellbeing to make a strong argument with property owners on this issue.” |

For those in delivery of building services, the focus of wellbeing is very much on the first layer of ‘comfort’. LG’s Andrew Slater says: “I think wellbeing has been around for quite a long time, but we don’t realise it has been applied in a lot of circumstances. We start looking at noise, air filtration rates, temperature ranges – the general traditional building design qualities. Now we are seeing there is a growing focus on how those things are affecting people, rather than just being an aspect of the building design itself.”

Andrew Robinson adds: “I suppose the issue of wellbeing for us depends on the project. If we are working on a hospital or care home, then there are very clear instructions on matters such as air changes or temperature requirements.

“A lot of the time we work on office projects and we see conditions on air quality, noise and temperature. They are aiming for a good working environment, including points such as a lack of draughts. These factors all lead into occupant ‘wellbeing’,” he adds.

These definitions go some way to demonstrating that measuring wellbeing is fairly challenging in that there are both objective and subjective factors to consider. Unlike energy measurement, for example, the approach has to be both quantitative and qualitative. Clements-Croome cites the Warwick Edinburgh assessment model of wellbeing.

|

|

Professor Derek Clements-Croome: “There have been many attempts to define wellbeing and they generally all point back to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs published in 1943. It encompasses the physical, social and mental wellbeing of people. It’s not confined to one particular area.” |

“It consists of an exhaustive set of questions which overs practical issues such as temperature, draughts and so on. But it also looks at higher order issues such as whether they feel happy within a space. It is possible to bring together these physical and psychological factors,” he says.

The panel agreed that the development of wearable monitoring technology that has become so common today is proving useful for checking on an occupant’s physical status. Andrew Slater adds: “It’s also possible to monitor Twitter and social media for mentions of phrases such as ‘too hot’ or ‘too cold” and match this with GPS information to find information on how occupants are responding to their environment.”

To support the growing interest in wellbeing, or aspects of it, there have been a number of studies and voluntary standards springing up. The Building Engineering Specialists Association (BESA) is particularly focused on the issue of indoor air quality and has launched a campaign called ‘Safe Havens’.

Jack Friend, managing director of training company Hasman and member of BESA, says: “With Safe Havens we are trying to develop a measurable standard that we can achieve in buildings so that they become areas that protect occupants from external pollution levels. We are looking at existing work on parameters such as air quality and particulates and bringing that thinking together.”

|

|

Dr Graeme Sherriff: “What I have found in my work is that the big challenge is ensuring people understand the technology that is being provided for them, so they can get the most out of it. ” |

He highlights an important challenge with air quality measurement: “The issue we have is the awareness of occupants in the building. A lot of the things we’ve spoken about such as greenery, lighting and temperature are easy for them to see and be aware of. But very often we find that occupants aren’t aware of a decrease in air quality which actually has a massive impact on their productivity and sickness absence.”

In its work in the domestic sector, BESA’s Safe Havens group has used an air quality monitor known as Foobot. “These monitors can detect trends in air quality changes in the home over time. We are then aiming to bring together research on how that affects occupants’ sleep and general wellbeing. Ventilation might otherwise be something they’re simply not aware of,” says Friend

And in the wider property sector, schemes such as WELL (developed in the US) are being more widely applied. WELL is a performancebased standard for measuring factors in the built environment that impact on occupant health and wellbeing.

Here in the UK, the British Council for Offices (BCO) is close to completing its major research study into health and wellbeing in offices. Derek Clements-Croome is one of the group working on this project. He says: “This report will lay out a number of points on the direction we should go in terms of wellbeing and we have highlighted our recommendations. This is also going to inform the next BCO Guide to Specification.”

|

|

Andrew Robinson: “The issue of wellbeing for us depends on the project. If we are working on a hospital or care home, then there are very clear instructions on matters such as air changes or temperature requirements” |

Clements-Croome also points out that government will be looking at this report closely and has already been taking the issue of wellbeing in buildings very seriously.

However, it has to be acknowledged that the construction industry has to exist in a business where cost and profit are very much to the fore when it comes to making decisions about building design. And this is where we come to the barriers to adding wellbeing elements to both commercial properties and homes.

Jonathan Moore says: “The impact of wellbeing considerations on design will very much depend on who is the client. If someone is building a speculative office to rent or sell, wellbeing will be low on their agenda. If a client is building an office that they will occupy, the will be more likely to be concerned about their staff wellbeing and that becomes a very different set of criteria.”

One of the other challenges is that current legislation that focuses on energy efficiency can often be at odds with what’s required for better occupant health and wellbeing. However recent research from Harvard shows sustainable buildings are more likely to be healthier than those that are not.

“We find that overheating of apartments is an issue at the moment,” says Moore. “Part L of the Building Regulations focuses on air tightness and U-values, so really what you’re building is a greenhouse. If the occupants saved £50 a year on heating bills because of air tightness, they’d be prepared to spend that £50 to not have a flat that is 45oC in summer.”

|

|

Jonathan Moore: “Wellbeing has to be balanced with regulations. I can give you more air flow, but the ducts and AHU will be twice as big, so we’re unlikely to pass Part L” |

Graeme Sherriff concurs that a potential clash of design requirements is an issue that has to be dealt with carefully: “In discussion research on a regeneration project in Salford, there was a lot of interest in air quality, related in part to the cladding and air tightness work that featured in the design. We rarely used the term ‘wellbeing’ but we talked about it in terms of other factors including IAQ and health.”

However, in the office market, for example, higher ventilation rates are not always practical. Moore says: “I saw a report that said absenteeism can be reduced by 50% by doubling the air flow rate into an office area.

“But we already have a challenge to meet specific fan powers for Building Regulations. Also, ceiling voids are getting smaller because everyone is pushing for higher ceilings. You couldn’t legislate that you need 20l/s per person without changing your specific fan powers, and it’s not possible to do without more space in the ceiling. I can give you that flow rate, but the ducts will be twice as big and so will the air handling unit so we’re unlikely pass Part L.”

But new technology is creating opportunities for providing more of the elements of wellbeing. Andy Slater highlights developments in thermal comfort: “LG now has systems that give individuals more control over their local environment, providing not just a set temperature, but actual thermal comfort with no draughts by providing a consistent thermostat on condition. We’re also reducing the amount of dehumidification down to 40% to 60% relative humidity, reducing issues such as dry eyes. It’s not just about energy efficiency, but delivering aspects of wellbeing.”

Absenteeism and presenteeism costs are high in the UK and amount to about £100bn per year, so we need to assess the value of new technologies, including the impacts of solutions on health and wellbeing, as part of the economic case.

|

|

Jack Friend: “With Safe Havens we are trying to develop a measurable standard that we can achieve in buildings so that they become areas that protect occupants from external pollution levels. ” |

Andrew Slater says: “With the MEES legislation, landlords won’t be able to rent out properties that fall below an energy efficiency standard, so they have to take action. Without a similar standard on wellbeing that says, ‘You have to meet these criteria’ you can’t make a strong argument with property owners.”

One way to highlight the value of certain approaches to building services for wellbeing is through simulation modelling. “Until legislation comes in, I think simulation modelling is an important thing. It is difficult to simulate some of the aspects of wellbeing we’ve discussed, but you can certainly model some of them so that the simulation is within 2% of the actual performance. For example, we offer computational fluid dynamics to show temperature, air flow and noise. That way you can show the client the impact of design decisions, and their benefits, over a long period of time,” adds Slater.

The panel agreed that winning client buy-in is key. Graeme Sherriff says: “The big challenge is ensuring people fully understand the technology being provided for them, so they can get the most out of it. Without buy-in there can be unintended consequences, such as high costs to tenants. In one project in Greater Manchester, I witnessed first-hand the challenge of working with residents to help them get the best out of technologies such as heat pumps, that require a different approach from users to conventional systems.

“They were used to turning off their central heating to save money, but with an ASHP that costs more when they’re turned back on. Additional costs such as these can have a major impact on their wellbeing as it can cut into their food budget, for example. The heating system was installed with the best intentions of improving thermal comfort and affordability, but in some cases it impacted negatively on this and other aspects of wellbeing.”

All agreed legislation is necessary. As Jonathan Moore says: “We need legislation to create a basic standard of wellbeing that every property developer has to meet in order to ensure it’s not just for those who can afford it.”

Sherriff agrees: “There is a social justice element in all this. If it’s only the wealthy, or those who own their own homes, who can get their home up to a good standard that doesn’t work. If you’re in the private rented sector you have little control over your home and your landlord has no incentive to improve it. We need to think about how wellbeing reaches across these groups.”

Health and wellbeing are for everyone and can result in higher productivity, higher staff retention and increase built asset value. We need a change of culture and ways of thinking.