Breathing easier

As concern grows over rising traffic air pollution levels, authorities are responding urgently to the pressing need for action to protect people, especially those in cities. But what can building services professionals do to help? Peter Dyment explains.

The notorious London smog of December 1952 was the single most deadly air pollution tragedy in UK history. A jawdropping 12,000 people were killed after inhaling a lethal cocktail of sulphur dioxide, smoke particles, carbon dioxide and hydrochloric acid and a further 100,000 were taken ill.

Alarm over the scale of death and misery caused by this catastrophe (which became known as the ‘Big Smoke’) led to the Clean Air Act of 1956. This pioneering law offered a series of measures to reduce air pollution, one of the most important of which was the introduction of smoke control areas in certain towns and cities.

Although the legislation helped ease the problem of poor air quality, it failed to eradicate it altogether; even today, more than 40,000 fatalities annually can be attributed to exposure to outdoor air pollution in the UK, with more linked to indoor pollutants.

Two critical facts together make a compelling argument for greater action to protect people from the harmful (and potentially terminal) effects of airborne pollution – first, we typically spend about 90% of our time inside buildings; secondly, there is an intrinsic link between outdoor and indoor air pollution.

I see no reduction in the levels of this pollution in the foreseeable future – the government has said that it will be 2030 before any significant decrease and, even then, the experts think it will be well beyond that time before we reach anywhere near safe levels of ambient pollution.

|

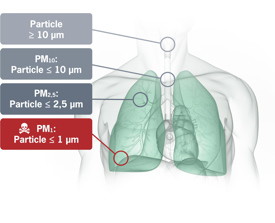

ISO 16890 – Measuring the efficiency of filters A new air filtration standard, ISO 16890, is set to replace the current European standard EN 779 in June 2018. This heralds a radical change in the way air filters are evaluated because ISO 16890 considers particle size ranges from 0.3 to 10 micrometers and is therefore far more accurate than its predecessor. Particle sizes ranges and profiles are derived from the typical dispersion concentrations found in urban and rural locations. The filter test takes into account the actual airborne particle sizes. Particulate matter (PM) affects more people than any other pollutant. PM comprises a complex mixture of solid and liquid particles of organic and inorganic substances suspended in the air. Its major components are sulphate, nitrates, ammonia, sodium chloride, black carbon, mineral dust and water. • PM10 is the fraction of all airborne particles =/< 10 microns (μm) in size. • PM2.5 is the fraction of all airborne particles =/< 2.5μm in size. • PM1 is the fraction of all airborne particles =/< 1μm in size (1μm = 1/1,000th of a millimetre).

Man-made PM is typically produced in areas of high population density in city centres. A big contribution to the concentration of ultrafine airborne particles (PM1) comes from diesel vehicle exhaust fumes. ISO 16890 classifies filters into four groups – PM1, PM2.5, PM10 and coarse dust (ISO coarse). To be assigned to a specific PM classification, the filter needs to stop at least 50% of the corresponding particle size range. Filters that capture less than 50% of PM10 particles are designated as coarse dust filters. |

That begs an obvious question – is there an alternative approach to defending people against airborne pollution? The obvious strategy is to use buildings as ‘safe havens’ to shelter individuals from exposure to harmful traffic contaminants.

And the need is urgent – the European Commission has just referred the UK to the Court of Justice of the European Union for its failure to comply with limit values for nitrogen dioxide (a major constituent of traffic fumes).

Indeed, the government is coming under renewed pressure to introduce a new Clean Air Act to tackle the UK’s toxic levels of air pollution. The Clean Air in London campaign and Baroness Jenny Jones, the Green party peer, have released a proposed clean air bill calling for breathing clean air to be a human right.

Separately, the Institution of Mechanical Engineers has called on the government to introduce “a modern Clean Air Act, equivalent to the one produced in the 1950s, in response to London’s Great Smog, in order to reduce harmful emissions across the UK”.

Small but deadly

We must ensure our homes, businesses, hospitals and schools are places where it is safe to breathe. I carry out training for consulting engineers, designers and specifiers and bring with me with me an air monitor which I like to turn on when I visit these places. Particulate matter below 10 microns in diameter is invisible to the naked eye and what is out of sight is also far too often out of mind.

There are two main types of traffic air pollution – fine combustion particles and toxic gases, in particular NO2. The WHO has labelled these types of pollution ‘group 1’ contaminants – the highest level of toxicity it ascribes. They are carcinogenic and cause cardiovascular disease as well as the early onset of Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia, so it is critical that there is something in place to protect people.

Thankfully, there is a solution – air filtration. New standards have been published recently referencing improved air filter testing and the selection of air filters for particular types of pollution. One of these – EN16798-3 – identifies 14 categories of building air, in particular outdoor air and supply air which are the two most important categories with regard to air entering buildings through ventilation systems.

Buildings, especially those in cities, must be ventilated. The problem is that there is no option but to bring outside air, often containing toxic particles and gases, into the building.

This is where filtration can play a critical role in protecting people. The building envelope has become increasingly airtight over the years. The fact that many modern buildings are sealed and employ effective filtration makes them ideal havens against the effects of outside air pollution.

Peter Dyment is technical manager of Camfil