Tracing the progress of CHP

Good-quality CHP can reduce primary fuel consumption by over a third compared with the separate provision of heat and electricity. Ian Hopkins of Ener-G Combined Power looks at its many benefits and its influence on building services engineering.

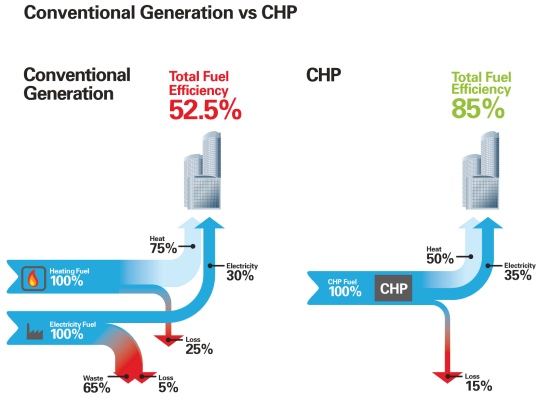

At the risk of over-generalising, the world of CHP used to be relatively simple and dominated by large-scale installations, usually with natural gas as the primary fuel. These installations were able to benefit from their improved efficiency, both in terms of energy costs and carbon-use. Over the past decade, CHP technology and engine efficiency has improved dramatically, with smaller-scale systems now typically achieving up to 85% fuel efficiency (see diagram).

Consequently, the benefits of CHP have become accessible to a much wider range of buildings, wherever power and heat requirements are in the right proportions. Rising power prices have also played a part in increasing the ROI (return on investment) of CHP at the smallest scale.

Wherever there is a large heating/cooling demand over extended periods, the cost and carbon saving benefits of combined heat and power (CHP) are difficult to match. This applies equally to new build or retrofit projects, particularly when looking to replace existing boiler plant or as an addition to new or existing boilers. An added benefit, is that CHP units can be configured to provide off-grid resilience to improve energy security.

There has been growing recognition that buildings with significant cooling demand represent another source of benefit for a CHP scheme, particularly where this cooling demand gradually replaces space-heating demand seasonally. CCHP (combined cooling, heat and power), also known as trigeneration schemes, have grown in prevalance to access this third energy/carbon-saving element and the rise in demand for air conditioned buildings.

In some cases, CHP schemes have exploited further cost savings from their outputs —for example, cleaning carbon-dioxide emissions and using them as an ingredient in soft drinks.

Whilst large-scale CHP has historically gained income from exporting to the grid, rising power prices have made it an important income stream for a much wider range of CHP schemes.

|

| Primary fuel is used over 60% more efficiently by CHP compared to the separate provision of heat and electricity. |

Improvements in metering technology, including the early stages of roll-out of smart meters, have influenced CHP schemes in two key areas — pre- and post-construction. Assessing the feasibility and economic case for CHP for a building relies crucially on accurate data regarding energy inputs and outputs. In the operational phase, quality data will facilitate efficient 'fine-tuning' of the CHP scheme and may give early warning of technical issues or compromised efficiency.

The introduction of a raft of financial incentives by the Government to support de-carbonisation of the energy sector has made the economic case for CHP even more attractive. Today's fiscal incentives include reduction or exemption from the Climate Change Levy, qualification for Enhanced Capital Allowances, preferential treatment in the EU Emissions Trading Scheme, exemption from business rates and exemption from the proposed Carbon Price Support Levy. In the right circumstances, CHP can yield a return on investment within three to five years — providing impressive cost savings over a typical 15 years+ product lifecycle.

To gain access to these fiscal incentives, schemes need to be certified as ‘good-quality CHP’ under the Combined Heat & Power Quality Assurance programme (CHPQA). This voluntary initiative, provides a methodology that assesses CHP schemes for energy efficiency and environmental performance.

A further development encouraging the uptake of CHP has been the availability of energy-performance contracts, such as Ener-G's discount energy-purchase scheme, which makes the technology and energy cost savings from CHP available without capital investment.

The introduction of sustainable building standards, such as BREEAM, has encouraged the use of CHP. Appropriate use of CHP schemes in both new-build and retrofit projects can make a big contribution towards the achievement of a high rating under this method.

|

| Ener-G installed this trigeneration system at the Museum of Liverpool, creating a new energy centre in the historic Great Western Railway Goods Shed on Liverpool's iconic waterfront. It incorporates two 385 kW bio-diesel CHP units, two 768 kW natural gas CHP systems, two 850 kW boilers, a 1000 kW absorption chiller and a 998 kW conventional compression chiller. |

Gas-fired CHP is widely regarded as one of the lowest-cost carbon-abatement technologies due to the significant primary-energy savings that it can deliver.

The introduction of Government sustainable building policies and renewable incentives has also influenced the installation of CHP schemes using a wider range of primary fuels — including biomass, biogas and bio-diesel .

The future for CHP schemes for buildings is positive — driven by the impressive efficiency, cost and carbon returns, together with the increased demand for energy security. On-site generation provides the double benefit of taking control of the security of power supplies, while reducing the impact of increases in wholesale market power prices.

While Government has made proposed adjustments to the financial incentives from large-scale CHP, the tax benefits for appropriately sized and fuelled CHP schemes remain attractive and, combined with continuing efficiency improvements, mean that CHP should come under consideration whenever a building’s energy strategy is reviewed.

Ian Hopkins is sales and marketing director for Ener-G Combined Power Ltd.