Delivering projects more efficiently

When the whole project team agrees on who does what, uncertainty, duplication of effort and confusion are reduced — so that projects are delivered more efficiently. DAVID CHURCHER explains how BSRIA is helping the process.A framework for building-services design activities can help all members of the project team by clearly setting out which tasks each organisation has agreed to do and which deliverables each organisation has agreed to provide. These principles are not restricted just to building services but can also be applied to other disciplines.

Starting point A schedule of design activities is one starting point for reaching agreement amongst a team of consultants, contractors and manufacturers on who will be doing what. Another starting point is a schedule of things to be delivered by one team member to another, such as drawings, calculations and reports. These two approaches are similar to using procedural or performance specifications, and they need not be mutually exclusive. A schedule of deliverables will concentrate on high-level concerns, since each deliverable will require the completion of a whole range of more detailed tasks. In contrast, a schedule of activities can be as broad or as detailed as is required and gives the opportunity for very specific items to be included so they are not forgotten, as well as broad-brush items that may define the entire role of a specialist designer or installer. There are also differences in the ways that schedules of activities and deliverables are used in practice. The schedule of design activities will be useful to consultants or contractors to help them work out their fee proposal or cost base for a particular project, whereas the schedule of deliverables will be useful to clients, project managers and lead consultants to help them make sure that all deliverables have been allocated to someone on the project team. In short, both approaches to managing and co-ordinating design activities have value.

Design framework Consequently, BSRIA’s recently published design framework for building services contains information on the following. • Overview of design deliverables expected at successive stages of a project and how these align with the RIBA Plan of Work and varied forms of commission for consultants available from ACE Agreement B2. • Flow chart of how different types of building-services drawing relate to one another in terms of what level of detail and what information they contain. • Set of definitions of the most commonly used types of building-services drawing, together with sample drawings illustrating each of the definitions. • Set of pro-formas setting out design activities for each stage of a project, including some which are often overlooked and some which are in the grey areas that cause conflict between consultant, contractor and manufacturer.

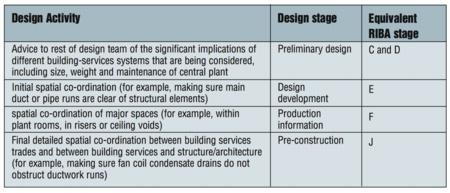

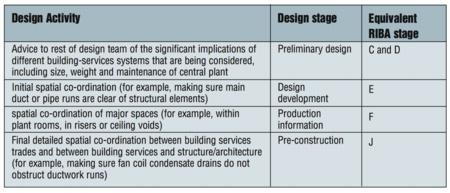

Spatial co-ordination is a traditionally grey area that is tackled in BSRIA’s design framework, and this iterative approach is suggested.

As well as linking with the current editions of the RIBA Plan of Work and ACE Agreement, the BSRIA design framework also takes account of the changes being considered as part of the forthcoming Consultant’s Contract from the Construction Industry Council (CIC). The CIC document has recently been out for consultation and is expected to be published towards the end of 2006. Some of the most significant developments reflect changes within the RIBA Plan of Work, including new definitions for the RIBA stages and removing the stages associated with tendering (stages G and H) from the strict sequence of other stages. Another major change is the acknowledgement that stage F (production information) overlaps with stages J and K (mobilisation and construction). All these changes will enable the RIBA Plan of Work to more closely reflect the sequence of events that occur on newer types of projects such as design and build, construction management and projects involving integrated teams and supply chains.

Grey areas Some of the grey areas that BSRIA has grappled with in its design framework are those of spatial co-ordination, energy modelling and Part L compliance, and when builders work information is produced. Each of these areas of design, in common with many others, can be thought of as an iterative progression from the general to the particular. For example, we suggest that spatial co-ordination involves the aspects highlighted in the table on the facing page. The sequence in the table is iterative since design changes within building services or in other disciplines may require earlier decisions to be revisited. Similar sequences for other areas of design are built into the detailed pro-formas in the design framework document. The detailed definitions of what information is contained in a particular type of drawing, together with a detailed list of which building-services systems are to be included in the project under discussion, mean that a detailed matrix of which organisation will be producing each drawing for each system will result. Of course this level of detail may not be required, but at least the option is there in the BSRIA pro-formas. The drawing definitions will make it clear to everyone involved in a project that sketch layouts will show locations and approximate sizes of plant rooms and main distribution routes, whereas detailed design drawings will show accurate sizing for ducts and pipes, and outline wiring specifications. Co-ordinated working drawings will include accurate layouts, including space for fixing, commissioning and maintenance. The result of having this design framework available so that precise points of information handover can be identified between services consultant, contractor and manufacturer may mean that the consultant agrees to take a project to the end of design development, and everyone else knows precisely what this means in terms of the detail of calculations the consultant will have done and the detail of drawing and specification that will be delivered. The outcome for the project is less scope for misunderstanding, with corresponding improvements in project efficiency and time and cost savings, which will benefit everyone involved including the client.

David Churcher is manager for construction improvement with BSRIA. www.bsria.co.uk References Churcher D (2006), A design framework for building services, BSRIA, Bracknell RIBA (1998), Plan of work, RIBA Enterprises, London Association of Consulting Engineers (2002), Conditions of Engagement — Agreement B(2), ACE, London

Related links:

Related articles: