Making Part L work

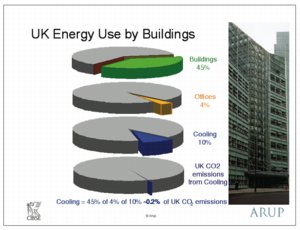

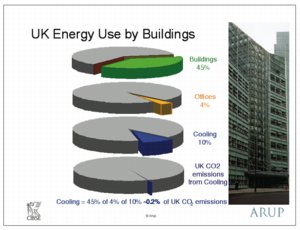

Serious issue or not? Cooling in office buildings in the UK represents only about 0.2% of carbon-dioxide emissions from buildings.

It is nearly a year since the publication of the 2006 Building Regulations, and the 12-month transitional period is nearly over. How well are they working? A recent CIBSE seminar sought to find out.As Part L of the Building Regulations working? Is Part L not working? Both opinions were expressed vigorously at a recent CIBSE seminar, which was organised in response to the steep learning curve presented by the changes last year to Part L of the Building Regulations — the section concerned with the conservation of fuel and power.

Carbon targets This fundamentally new approach to the Building Regulations is necessitating designers having to learn how to meet whole-building carbon targets for new buildings that are not dwellings (Part L2A) — aided by the freely available SBEM (Simplified Building Energy Method) and the various commercial software packages. Likewise building operators are also having to learn how to meet the requirements when works are carried out in existing buildings. As designers start to get to grips with delivering buildings that comply with Part L, some perhaps surprising issues emerge. In his analysis of the impact of the regulations on system selection, Terry Dix, a director with Arup, suggested that it is easier to pass an SBEM analysis with an air-conditioned building than with one based on natural ventilation. His logic is based on the fact that air-conditioned buildings are required to have a carbon footprint 28.0% lower than the notional building complying with the 2002 Building Regulations, compared with 23.5% less for a naturally ventilated building. With the energy efficiency of air-conditioning having increased by 50 to 60% in the last five years or so, making COPs of 4 to 5 at part-load operation commonplace, that 28.0% target figure should be readily achievable. Indeed, Terry Dix says that a COP of 4 will do the job. In contrast, the only areas in which to make savings with a naturally ventilated building are improvements to the building fabric, more efficient heating systems and more efficient lighting. Continuing with the problems associated with naturally ventilated buildings, Terry Dix explained that they are harder to design and do not have the potential to benefit from heat recovery — unlike the increasing number of heat-recovery VRF air-conditioning systems, for example. Likewise the requirement that indoor temperatures should not exceed 25°C for more than 5% of the occupied period and that they should not rise above 28°C for more than 1% of the occupied period must draw designers towards air-conditioned solutions — especially with summers in the UK getting hotter. However, since the raison d’être of the new Building Regulations is to make a major contribution towards reducing the UK’s carbon emissions by 60% by 2050, buildings designed for natural or mechanical ventilation appear in quite a different light. Quite simply, as Terry Dix points out, naturally ventilated buildings use less than half the energy of those that are air conditioned. The detailed figures are instructive.

CO2 emissions According to Terry Dix, a typical naturally ventilated building emits 26.0 kg/m2 of carbon dioxide a year, which has to be reduced by 23.5% to 19.9 kg/m2. The typical figure for mechanical ventilation is 36.7 kg/m2, which has to be reduced by 28.0% to achieve 26.4 kg/m2. The 67.8 kg/m2 for an air-conditioned building has to be reduced by 28.0% to 48.8 kg/m2. ‘Maybe natural ventilation was too good before,’ suggests Terry Dix. Yet another significant aspect of the Building Regulations and vital to achieving planning permission in many areas is the use of renewable energy, as both Terry Dix and Ant Wilson of consultant FaberMaunsell pointed out. A 10% requirement for renewable energy amounts to twice as much for an air-conditioned building as for one that is naturally ventilated — a saving which could be put into designing and building a naturally ventilated building. But why all the concern with the energy ‘guzzled’ by air conditioning. Terry Dix has an interesting set of figures. First, buildings account for 45% of the energy used by buildings in the UK. Secondly, offices account for just 4% of the energy used by buildings. Thirdly, cooling represents 10% of the energy used by buildings. Put those figures together, and you arrive at the conclusion that the energy used for cooling offices in the UK accounts for less than 0.2% of carbon-dioxide emissions. A way to make a large dent on that 23.5% reduction in carbon-dioxide emissions from new buildings (not dwellings) was highlighted by Ant Wilson. A perspective on the new Part L from the Department of Communities & Local Government (formerly ODPM) highlights three enhanced management and control features that reduce the amount to be saved by other means. • Automatic monitoring and targeting, with alarms for out-of-range values carries an adjustment factor of 5%.

• Power-factor correction to achieve at least 0.9 for the whole building carries a 1% adjustment factor.

• Power-factor correction to achieve at least 0.95 carries an even better 2.5% adjustment factor. As Ant Wilson points out, combining automatic monitoring with a power factor of 0.95 immediately reduces 23.5% to 16% — and can be achieved with just one line in the specification.

Wood burning One person who has welcomed the opportunities offered by the new Building Regulations for the role of the role of the architect and engineer to be reversed is Dick Bradford of Barnsley MBC. He is principal designer (building services) and energy engineer with the council and has been involved in making Part L work in the design and construction of new buildings for the council. Westgate Plaza One is the new headquarters building for Barnsley Council. The environmentally friendly features of this 5-storey building include heating fuelled by biomass and rainwater harvesting.

|

| — Renewable energy in practice — the Westgate Plaza One offices of Barnsley MBC are heated using wood chips — displacing 1400 MWh of gas a year and achieving a payback within four years when lower fuel costs and capital costs are considered. (External photo Associated Architects) |

But it is the use of wood-chip fuel for heating that is most noteworthy. These wood-chip boilers are carbon neutral, returning to the atmosphere the carbon dioxide absorbed when growing. Nor is this zero-carbon approach to space heating more expensive than using gas, for the payback is quite quick. Dick Barnsley explained that the 500 kW wood-chip boiler can serve both phases of the development and also service the town hall and central library via accumulator vessels at night. He says that the capital cost of natural-gas boiler plant would have been £18 000, compared with £150 000 for the wood-chip plant. However, the annual fuel cost for gas would have been well over double the capital cost — £45 500, based on 1400 MWh at 3.25 p/kWh. In contrast, the annual cost of wood chips is £12 000, amounting to 350 t at £35 per tonne. The simple payback of the wood-burning plant compared with gas is just under four years. Assuming a 25-year life, the saving is £758 000. With this level of return on investment and carbon-dioxide savings achieved, the policy of Barnsley MBC is firmly towards biomass heating — unless a business case can be presented otherwise. Indeed, Dick Bradford sees the existence of Part L as being the key to utilising such LZC technology.

Planning permission Because the new Building Regulations are not prescriptive, building control officers with local authorities could often find themselves without all the skills to assess a project for planning permission. One solution, as Ant Wilson explained, is to work with a ‘competent person’ registered with one of the five approved schemes, including BESCA for buildings other than dwellings (www.besca.org.uk). Ant Wilson explains that it can be far cheaper to work with a competent person to get a building signed off and that Building Control will need to accept this approach. More insight came from Barry Turner, technical director with Local Authority Building Control, a publicly accountable, independent building-control provider. He expressed the belief that a local authority is authorised to accept a certificate from a competent person, but does not have to. However, he recommended that if a competent person is involved with the planning process talking to the local authority first so that everyone involved can be confident that the required energy savings will be achieved.

Not a minimum standard Looking beyond the practical issues of the day and towards the future, Phil Jones, chairman of CIBSE’s Energy Performance Group, expressed the view, ‘Part L should be seen as a minimum standard. We need to strive for standards beyond Part L — which is where CIBSE’s register of low-carbon consultants comes to the fore. Part L is a minimum requirement, not a maximum.’ The register now lists some 300 trained and qualified low-carbon consultants, and their capabilities are developing. The register was launched in September last year and now consists of a design side and an operations side, which are soon to be joined by a simulation side. In five year’s time, the register is expected to list 5000 low-carbon consultants.

Related articles: