In search of zero-carbon non-domestic buildings

While politicians have been setting deadlines for new buildings in the UK to be zero carbon, it is engineers that have the task of delivering. They have been looking deeply into the issues, as was very evident at a CIBSE event.

The timetable for new buildings in the UK to be zero carbon is well known. By 2016, new homes built in the UK will be required to be zero carbon. The date for non-domestic buildings is 2019 and a year earlier, 2018, for central-government buildings, hospitals, prisons and the defence estate. What is less clear, however, is what zero carbon means and how zero-carbon buildings, whatever they are deemed to be, will be achieved.

It was against that background that a CIBSE event addressed the question of zero-carbon non-domestic buildings and how low it is possible to go. Phil Jones, chairman of CIBSE’s energy performance group and research fellow at London South Bank University summarised the uncertainties. ‘What is a zero-carbon building? Can we achieve it? Is it possible at all? Can we really get to zero-carbon buildings?’

Questions like that suggest it might not be possible to go very far at all towards zero-carbon non-domestic buildings. But Phil Jones was not deterred, asserting, ‘It is down to us to make zero-carbon-buildings happen — whatever they are.’

But even as the industry endeavours to identify and get to grips with what is required, it is hampered by, quoting from the Government report ‘Low carbon construction’ prepared by the low-carbon construction innovation and growth team chaired by the recently appointed Chief Construction Adviser Paul Morrell, ‘the plethora of policies, reports and initiatives, undertaken by a variety of Government Departments, or by NGOs or other special interest groups, which are incapable of absorption by businesses who need to focus on the more immediate interests of their clients and shareholders’.

So what does zero carbon really mean?

Jules Saunderson of Mott MacDonald Fulcrum explained that for housing zero carbon means that over a year, the net carbon emissions from all energy use in the home would be zero. How to achieve zero net carbon emissions is also defined in a 3-stage approach. The foundation is to maximise the efficient use of energy. The next stage is measures such as on-site renewable energy and connected heat. The final stage is ‘allowable solutions’, which could include exporting low- to zero-carbon heating/cooling to existing properties, retrofitting energy-efficiency measures to existing stock and off-site renewable electricity via a direct physical connection.

The target for zero-carbon homes covers energy used by appliances as well as energy associated with heating, lighting and cooling. The two types of energy use are dubbed regulated (for heating, lighting and cooling) and unregulated.

In non-domestic buildings, however, unregulated energy will not fall within the scope of zero carbon. The Government believes this will be too difficult because the variation in energy use between different types of commercial and industrial buildings is so much greater than for homes.

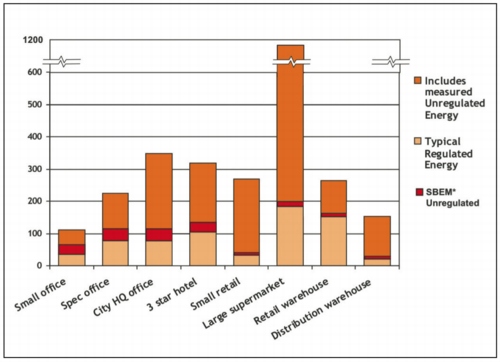

Just how huge is that variation between the use of regulated and unregulated energy, was explained by Chris Twinn, a director of Arup stressed. Fig. 1, from his presentation, shows the vast range of unregulated energy in buildings. In a large supermarket, for example, only about 15% of energy consumption is regulated, with much of the unregulated energy consumption being attributable to chilled- and frozen-food cabinets. Even at the other end of the scale, a retail warehouse, nearly 60% of energy consumption is regulated.

Within SBEM itself (Simplified Building Energy Model), there is an element of unregulated energy, as shown in Fig. 1, which varies from building to building. One suggestion from CLG is that unregulated emissions should be 10 to 20% of the target energy rating (TER). Sam Archer, associate director of AECOM’s sustainable-development group, suggested that while such an approach would be very easy to implement and understand, it would exclude some unregulated emissions, penalise some types of building and heavily benefit others.

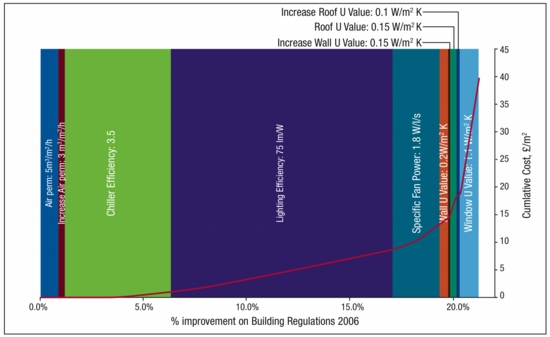

With energy efficiency being the foundation of achieving zero carbon, an analysis of the cost of a range of approaches for improving on the 2006 Building Regulations presented by Sam Archer was illuminating. His analysis was for a large city office and shows the order of cost effectiveness of a range of measures for carbon abatement (Fig. 2). It is clear that the cost of reducing carbon emissions by more than about 18% mounts up very quickly.

The potential of such energy-efficiency measures to reduce emissions is extremely reliant on the type of buildings.

Sam Archer explained that at one end of the scale are large supermarkets, with energy efficiency measures being able to reduce emissions by only 10%.

At the other end of the scale is a distribution warehouse, with 55% being achievable. A retail warehouse is close behind at 52%.

Closely grouped are small offices (38%) and hotels with ratings of two to five stars (33%).

Coming in at 21% are speculative offices, shopping centres and city-centre headquarters.

Finally, a mini-supermarket comes in at 14%.

Sam Archer also considered carbon compliance as an approach to carbon abatement for a standalone medium suburban office, but costs add up rather more quickly than energy-efficiency measures.

Advanced-practice energy efficiency can achieve a improvement on the 2006 Building Regulations of over 20% for about £40/m2 added to capital costs.

The addition of biomass heating can increase the carbon abatement to about 20% for a cumulative capital cost of about £50/m2.

Adding as much solar photo-voltaic to the roof as possible could increase the carbon abatement to over 45%, but see cumulative costs more than treble to about £170/m2.

If feasible, small-scale wind turbines to generate electricity could push the carbon abatement to a little over 55% and cumulative capital cost up to about £260/m2.

For this kind of medium suburban office, the additional benefits to be gained from biomass trigeneration and ground-source technologies diminish rapidly.

While reducing carbon emissions incurs costs initially, there are substantial savings to be made in the longer term — as explained by Chris Twinn, based on an analysis carried out by the Carbon Trust and Arup. That analysis compares the cumulative net cost against cumulative carbon saving for non-domestic buildings for reducing carbon emissions by 80% by 2050.

Even for a reduction of over 70% by 2037, there is no net cost. After that time, however, costs escalate rapidly to £13 billion by 2050.

Closer to the present, a 35% reduction in CO2 emissions by 2020 would have a net cost benefit of £4.5 billion.

The analysis comes with a warning that other scenarios, such as those which achieve less than 35% reductions by 2020, will have a different cumulative cost profile — all with a greater cumulative cost to achieve an 80% reduction by 2050.

Unfortunately, the financial benefits do not accrue to the organisation paying the cost.

While the agenda for the day was zero carbon in non-domestic buildings, it proved impossible to avoid discussing how to reduce carbon emissions from existing buildings. However, as building-services engineers are well aware, zero-carbon new build will mean nothing if emissions from existing buildings are not drastically reduced. In this context a suggestion by the UK Green Building Council that an allowable solution to offsetting residual carbon emissions from a new building should be the retrofitting of existing buildings could rather speed up the process of overall reductions in carbon emissions.