Delivering energy efficiency with district energy

Centralised energy centres serving district energy schemes are making a growing contribution towards achieving low and zero carbon buildings. Simon Woodward discusses the key issues for specifiers

As the drive to achieve low- and zero-carbon buildings continues, it’s important to remember that optimising the efficiency of the energy supplies will often achieve more than focusing just on headline-grabbing technical innovations. The latter have their place, of course, but ensuring that any energy consumed is delivered efficiently is the first step.

It is therefore important to consider how efficiently the ‘life blood’ of buildings — hot and chilled water and electrical power — is produced and delivered.

To that end, centralised energy centres containing low-carbon generation plant and coupled to district energy schemes are proving they have a key role to play in significantly reducing emissions and energy costs. In fact, members of the UK District Energy Association are already supplying over 600 GWh of low-carbon heating each year, and this is increasing all the time.

This success is because a central energy centre, or network of linked energy centres, can exploit economies of scale and the variable performance of different technologies at different loads. District energy schemes also increase opportunities for using low- and zero-carbon (LZC) technologies, exploiting economies of scale to increase the financial viability of such technologies. In this way, LZC technologies are included for sound engineering and environmental reasons, rather than simply to tick that particular box on a single-building basis — which is often at a small scale and sub-economic level.

Furthermore, this approach is no longer confined to large-scale projects such as the Olympic Park or MediaCityUK nor to city-wide schemes such as those in Birmingham, Leicester and Southampton. Improved heating technologies mean that district energy schemes are now viable in smaller projects such as housing/mixed used developments, including elements of retail and industrial parks, urban regeneration schemes etc. Also, despite misconceptions to the contrary, district energy schemes can be retrofitted to existing facilities.

In fact, many recent additions to the Birmingham and Leicester district energy schemes have been existing buildings that opted to take advantage of these benefits. One such example is the University of Leicester, which, after extensive evaluation, determined that connection to the Leicester district energy scheme was a more financially viable option than installing its own CHP plant.

District energy also scores highly in environmental assessment schemes such as BREEAM and LEED, and it facilitates compliance with Part L of the Building Regulations. It will also help to gain planning permission from most local authorities; indeed many actively require connection to a district energy scheme where available.

Building-services specifiers tend to get involved in district energy in two ways. They may be looking at specifying an energy centre and district energy network for a new development, or be asked to advise on the implications of connecting to an existing scheme.

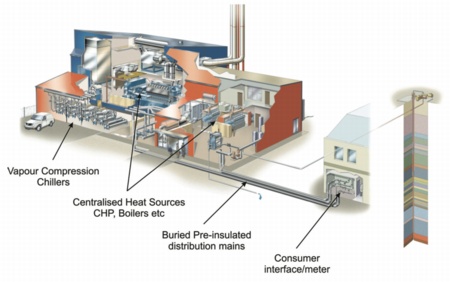

When starting from scratch, the key to minimising carbon emissions is to get the right balance of technologies. A typical energy centre serving a district energy scheme will have combined heat and power (CHP) at its heart, usually fired by gas. Where there is no clear local use for the electricity a biomass boiler might be used — or a combination of gas-fired CHP and biomass. Whatever LZC is chosen, it must always be sized to meet the base heating load through the year.

This plant may then be supplemented by conventional boilers at peak times. It is also important to consider the use of thermal stores to maximise the amount of energy used from the LZC generation plant, while minimising use of heat from gas-fired boilers. However, thermal stores must be correctly designed as there many examples of thermal storage that has little operational impact.

In tri-generation schemes that also generate chilled water, cooling can be generated in summer using waste heat from the CHP via absorption chillers, hence increasing utilisation of the CHP.

In all cases, the electrical power may be used on site or exported to the grid. Ideally it should be used directly via a ‘private wire’ to improve the economics of the scheme.

Furthermore heat, power and cooling can all be individually metered to separate buildings or zones for recharging purposes.

There are also now many opportunities to connect to an existing district energy scheme, in a city centre perhaps, offering a number of benefits.

First, in the context of achieving low-carbon buildings, users can expect to save 5 to10% on their whole-life-cycle energy costs, compared to running their own local plant. Participants in the Carbon Reduction Commitment Energy Efficiency Scheme will also save on the purchase of carbon allowances.

If the end user’s plant is nearing the end of its life, connecting to an existing district energy scheme will save up to 20% on capital costs compared to buying new plant. Plus the space previously used for plant will be freed up for other uses. It is worth noting that the temperatures and pressures used in district energy schemes are the same as those typically used in heating and cooling systems, so distribution systems and terminal units do not need to be changed. If the two systems are not compatible a simple heat-exchanger arrangement can be used at the building entry point.

So there are many sound reasons for including district energy as one of the options for a wide range of projects. As district energy schemes proliferate, there will be even more opportunities to connect existing buildings, which account for such a significant proportion of the UK’s carbon emissions.

Simon Woodward is CEO of Cofely District Energy and chairman of the UK District Energy Association.