Lightening the load

Dave Cooper looks at the heavy load of documentation, legal obligations and standards to be reached at the varying stages in the life cycle of a lift and shares his experiences in the field of lift maintenance.

The responsibility involved and extensive range of documentary obligations required to manage a single lift, yet alone a portfolio of lifts, can be headache inducing. Adding to this burden is the variation of requirements depending on the environment(s) that the lift(s) operate in. Is the lift in an office block, retail outlet, airport, ski resort or any combination of these?

With the increasing shift towards litigation - personal accident claims and contractual disputes – it’s exceptionally important to get it right from the outset.

The life cycle and how to cope with obligations

To ease the throbbing pain of understanding the documentation trail, it is important to understand the phases in the life of a lift. These phases vary depending with the type of equipment installed and whether it was of sufficient quality for the environment it is installed in.

As a high capital cost item, early replacement of the lift means an early high capital spend as well as the interruption that goes with it. In a retail environment this can have a direct effect on sales, reputation and ultimately affects the rental value of a building. I

This simple matrix is a good place to start:

| Well Installed | Badly Installed | |

| Appropriate Quality | Maximum Longevity | Reduced Longevity |

| Inappropriate Quality | Reduced Longevity | Disaster |

The ‘well installed’ and ‘appropriate quality’ box is where everyone should be. The message is simple - getting it right at the outset is crucial. To ensure you achieve this, it’s important to understand the life cycle of a lift.

•Installation phase

•Service phase

•Modernisation or New Installation phase

•Service phase

It is at the installation phase where the matrix above is vital. You can employ a consultant to assist you, but even here it is a bear pit with a large number of lift consultants being sales-biased rather than qualified engineers offering you truly independent advice.

You will need a consultant that is independent and not receiving a commission from the lift contractor.

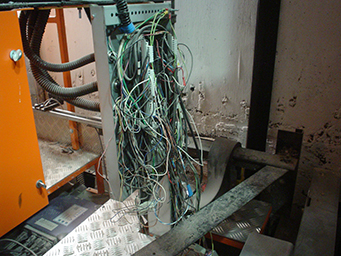

|

| Poor quality wiring in lift motor room |

Installation phase

During the installation phase you must ensure that the lift is compliant with The Lift Regulations and the easiest way to do this is to ensure compliance with the EN81 series of European Standards.

In recent months EN81-1 and EN81-2 (traction and hydraulic lifts respectively) have been replaced by EN81-20 and EN81-50. To ensure that the lift has actually been installed to the requirements of these standards there is a parochial British Standard BS8486 where a number of tests and checks will ensure compliance with the requirements.

However, there is a caveat: While this standard will make sure that components are functional, it may not always pick up on poorly installed components which is where a qualified consultant comes in. A new lift should also come with a Technical File as a requirement of The Lift Regulations. This will document how to operate, maintain and manage the lift in accordance with the manufacturers and designers’ requirements.

Service phase

Once the lift has been installed and handed over it enters the service phase. This is the time when the lift is simply in service doing what it was designed to do. It is at this phase when passengers are introduced into the risk profile and owners need to protect themselves against regular accidents such as being hit by doors, slips and trips, mid-flight stops and so on. A good start is to make sure that you have all of the appropriate documentation available and that you employ a reputable maintenance contractor.

It is alarming how many times I have encountered a lift owner not being able to lay their hands-on vital paperwork following an incident. During the service phase the requirements of the Lifting Operations & Lifting Equipment Regulations (LOLER) and the Provision & Use of Work Equipment Regulations (PUWER) may apply, as well as the overarching Health & Safety at Work Act. In addition, the Occupiers Liability Act and the Defective Premises Act need to be considered.

In 2006 the precedent was set that a lift in an office building falls under PUWER as the lift is only being used as part of an employee’s work. The lift needs to be maintained in good condition and a sound maintenance contract needs to be entered into. The maintenance should be appropriate in terms of what the contract covers and also the number of visits per annum that the contractor attends to undertake the maintenance.

Similar to servicing your car, this generally involves cleaning, adjusting and lubricating. Contracts vary and sometimes include the cost of parts and labour. However, some contracts simply undertake these requirements (cleaning, adjusting and so on) and anything else is chargeable.

|

| Flooded lift pit |

Similarly, a lift in a workplace has to be subjected to the equivalent of an MOT test. In the lift world this means LOLER - where a competent person will undertake a periodic thorough examination and issue a certificate. Passenger carrying lifts are normally subjected to six monthly examinations and non-passenger carrying lifts every 12 months. There is an option to vary this but it is rarely used.

During the service phase there is an additional requirement for supplementary tests. These first appeared in 1984 in a document issued by the HSE known as PM7 but were subsequently replaced by the SAFed LG document. It is recognised that the competent person undertaking the LOLER examination is unable to access or examine certain components and therefore the LG system allows them to call for supplementary tests on components such as gearboxes, shafts and pulleys, door locks, overspeed governors, safety gears etc.

After a few years in service, and the length of time varies with the appropriate equipment versus quality of installation, the lift will require attention. CIBSE guide D gives estimated longevity for lifts but also acknowledges that low cost budget equipment can give a reduced life span. In reality, I have seen this as low as just three years. However, on a general basis you could expect to get around 10 years out of a budget lift package and more for a better-quality design.

The lift will then go into a phase where modernisation or replacement is required. Replacement may seem drastic - particularly after a reduced longevity period where one would hope you could make do and mend. Unfortunately, if the lift was originally badly installed it will never be good and all you are doing is trying to achieve the clichéd silk purse out of a sow’s ear. If you don’t get the guides right in the installation phase the lift will never be right.

Modernisation or replacement

|

| Poorly installed overspeed governor with rope paying off badly |

The choice between entering a modernisation phase or going back to a new installation phase is often generated by reliability problems, component wear, obsolescence, a lease requirement and so on. This is the optimum time to seek advice from a well-qualified independent consultant. If the lift was installed after 1997 the modernisation needs to achieve the safety requirements originally met by its compliance with The Lift Regulations. If the lift was installed pre-1997 there is a standard known as EN81-80 (Improvement of safety of existing lifts) where an assessment should be undertaken to identify any areas where safety could be improved such as levelling, door protection and so on.

It’s a maze, but keeping a sound document management system is important to maintaining the lift to a good standard and being able to prove it in the event of an incident. Fortunately, incidents are reasonably rare but they do happen. From 38 years of experience in the sector, I have found that it’s always best to get advice from an independent engineering consultant – not only will you save time and money but it will greatly reduce the pain of ensuring your equipment is safe and sound in the long-term.

David Cooper is managing director of LECS and is co-author of The Elevator & Escalator Micropedia (1997) and Elevator & Escalator Accident Investigation & Litigation (2002 & 2005) and is founder of the Elevator Academy.