Bringing buildings back into use, safely

Toby Hunt from Guardian Water Treatment explains the potential problems posed by dormant water systems and how to safely bring a site out of mothballing.

A year on from the first lockdown, many of the UK’s city centre commercial buildings are still unoccupied. Hopefully, by the time you read this, we are slowly emerging safely back into the world. As the threat of coronavirus recedes, we must now consider the safety of the buildings that have lain dormant. It is not just a case of opening the doors, particularly when it comes to water-based services.

There has never been a stranger time in Britain’s city centres, usually a hub of bustle and life, for the past year they have become ghost towns. The offices, full of building services designed to be used, are empty. In many case this desertion was quick and unplanned, meaning the correct mothballing steps were not even taken. Even where they were, none of us thought this was going to go on for so long.

Whatever happens next, ‘work’ has changed forever, and it is likely that some of these buildings may never return to full capacity as more people than ever before ditch the office for good.

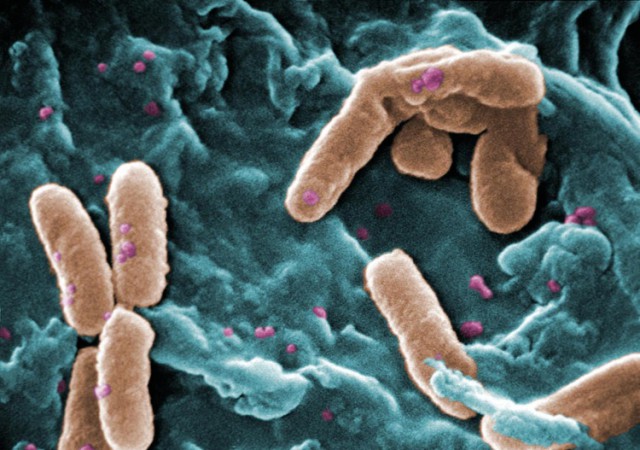

For the buildings welcoming back the hoards, it’s imperative that operations are returned safely. Unused water systems, for example, can be breeding grounds for legionella, the bacteria behind the potentially fatal Legionnaire’s disease – we don’t want to jump from one public health crisis to another.

Legionella likes stagnant water, which tends to increase where tanks and pipes are not flushed through regularly. Unfortunately, however, you cannot leave a system dormant and then simply flush it out before it’s ready to be used again. According the Legionella Control Association, reopening a building that has stood idle without addressing the safety of its water systems is unacceptable and likely to be in breach of the law.

During lockdown

Just because a building is empty, doesn’t mean essential servicing and maintenance has to stop. In fact, we have evidence that flushing buildings alone during periods of inactivity could serve to compromise general microbiological control.

We took over 30,000 samples from London buildings during the six months from April 2020 (first full month of lockdown). Most of the buildings in the sample were following manual flushing regimes. Results show a significant increase in failure rates across the board, for both Total Viable Count (TVC) samples and positive legionella results.

Comparing the results year-on-year, the data shows:

- The number of ‘out of specification’ TVC results (water samples that carry unacceptable levels of microbiological contamination) has risen by more than 50%.

- The rate of detection for positive legionella samples has also risen by around 20% in conjunction with the lockdown.

These results indicate that while flushing does help to prevent stagnation and legionella growth, overall microbiological control is likely to be compromised if flushing is treated as a stand-alone solution.

The right approach

The buildings that stand the best chance of a stress free return to usage are the ones that haven’t treated lockdown as a chance to cut back on essential maintenance. It’s clear that flushing alone is not enough, so what’s the right approach? In this first instance, water systems need to be reviewed to ensure compliance with Legionella Control document, ACoP L8.

The flushing through of water through pipes and taps, is part of the design and helps towards healthy and efficient operation, preventing stagnation – many of these empty buildings are designed for thousands of people. If a building is going to remain empty for long periods, reducing the locations where water can sit (and get warm) are key steps in preventing places for bacteria to thrive.

This can be achieved by reducing tanks and/or tank capacity. Water heaters can be turned off if hot water is not required - as long as the water is stored at less than 20˚C. And cooling towers, well-documented bacterial breeding grounds, must be tested as normal (weekly and in some instances daily). Where access is not possible, the cooling tower and associated systems can be shut down.

Regular sampling is essential, particular after periods of intervention. Drinking water in particular needs to be tested – after a long period of stagnation it may no longer be potable, which could also lead to delays in buildings re-opening.

To keep bacterial levels under controls, we recommend using chloride dioxide based chemicals when flushing. Treated water provides a constant low level defence that is far more effective than just using water alone.

HVAC health

Keeping bacterial levels in-check is not just a public health issue, it’s a HVAC health issue too. The build-up of bacteria, sludge and rust will lead to inefficiencies and potential breakdown. With many businesses taking a financial hit, paying for repairs on an expensive commercial water system is something to be avoided. Cutting corners with ongoing upkeep in this instance is a false economy.

For closed systems, we use 24/7 remote monitoring to check condition. This approach provides real-time information and prevents unnecessary site visits – something that’s all the more importance is we avoid travel and social contact to halt the spread of Covid.

Industry best-practice

Industry guide, SFG30, has been produced to help FMs and maintenance teams take the right steps when bringing a building safely back into operation – covering water and all the other critical building services. This is an unprecedented time in human and building history, so it’s important those responsible for restarting the wheels of office life do so cautiously and safely, utilising expert support and guidance.

Toby Hunt is Key Account Director at Guardian Water Treatment