Carbon Trust charts a route for reducing carbon emissions from non-domestic buildings

Non-domestic buildings emit about the same amount of carbon today as they did in 1990, hence the importance of a new report from the Carbon Trust on reducing emissions from such buildings.

If the 80% reduction in carbon emissions by 2050 (compared with 1990) required by the Government is to be met, all sectors of the UK economy must make their contribution. And that includes non-domestic buildings such as offices, shops, hotels, public-sector buildings and industrial buildings.

At present, such buildings account for 18% of the UK’s total carbon emissions — a figure that has been pretty well static since 1990 as a reduction in emissions at the rate of 0.5% a year has been offset by an increase in floor area of 3.7% a year. The overall result is that CO2 emissions peaked at about 88 Mt a year in 1991 and were about 80 Mt a year in 2006.

The process of reducing CO2 emissions from non-dom buildings, as they have been dubbed by staff at the Carbon Trust involved in researching and producing a new landmark report ‘Building the future today’* effectively starts now for the 1.8 million non-domestic buildings in the UK. And that report has found that it is possible to deliver carbon savings economically. If the right strategy is followed, the carbon footprint of non-domestic buildings can be reduced by 35% by 2020, compared with 2005 levels, and a net benefit of £4.5 billion delivered to the UK economy through energy savings.

That rate of reduction is well above the overall UK target of 21 to 31% — and much more could be economically achieved. The Carbon Trust’s analysis suggest a carbon reduction of 70 to 75% at no net cost to the UK.

Stuart Farmer is head of buildings strategy at the Carbon Trust and lead author of the report. He says, ‘Commercial and public buildings offer the UK a big bang for its carbon-reduction buck. But it won’t happen just on its own. Energy efficiency needs to be the first and second priority. For policy makers and business, rolling out Display Energy Certificates to all non-domestic buildings must be the foundation stone to deliver not only better buildings but better use of buildings too.’

Relying on the existing Building Regulations (2006) is not enough. While new buildings will have substantially lower carbon emissions than existing buildings, the rate of demolition is so slow that is reliance were placed on the 2006 Building Regulations alone, emissions would increase by 30% by 2050. The energy efficiency of existing buildings must be improved — and improved enormously.

Very helpful starting points in monitoring the energy performance of buildings are Energy Performance Certificates and Display Energy Certificates. Both certificates are graded A to G.

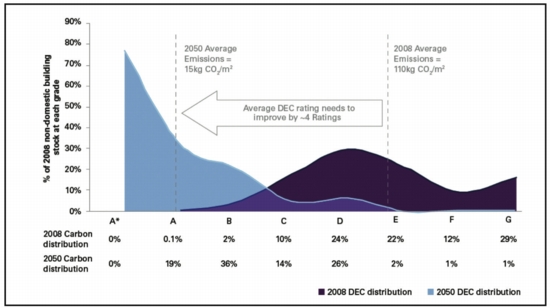

Not only is G the lowest grade, by it is also the biggest single group of Display Energy Certificates, comprising 29% of the building stock in 2008. 41% come in at F or lower, 63% at E or lower, and 87% at D or lower. Associated with these low DECs are average CO2 emissions of 110 kg/m2.

With the target for average CO2 emissions in 2050 being 15 kg/m2, a huge improvement in the energy performance of buildings is needed as shown in Fig. 1. In a nutshell, the average DEC of a building needs to improve by four ratings to achieve Government targets for reducing carbon emissions. That is equivalent to the current collective E rating improving to an average A rating.

Until that level of improvement is achieved, the report calls for all buildings to achieve at least an F-rated Energy Performance Certificate by 2020, where this is cost-effective.

At present, EPCs and DECs do not apply to all non-domestic buildings, and the Carbon Trust report calls for them to be rolled out across all non-domestic buildings. Not only will this result in better buildings, but also in buildings that are used better.

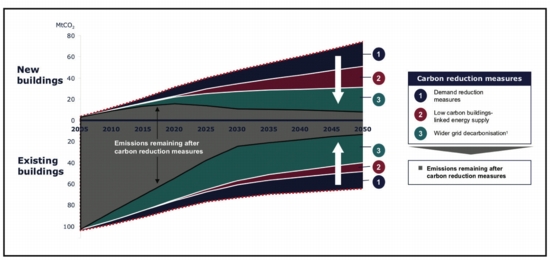

The objective of the Carbon Trust’s vision is to achieve 80% carbon reductions by 2050 at the lowest cumulative cost to the UK economy. The success scenario, as illustrated in Fig. 2, is based on a range of carbon-reduction measures. They include reducing demand, low-carbon energy supply for buildings (all based on renewable energy on, near or off site) and wider decarbonisation of the grid supply.

The sooner substantial progress is made, the lower the ultimate financial burden. In other words, reducing more carbon sooner will lead to a reduction in the cumulative cost of the 80% target of 2050 — even as low as no net cost.

Decarbonisation of the grid is seen as the key to reducing carbon emissions from buildings — especially existing buildings.

The long-term target of reducing carbon emissions by 80% requires all available technologies to be employed, but achieving the success scenario of the lowest cumulative cost requires close attention to the order in which they are applied.

The first stage is the implementation of simple, low-cost, cost-effective measures. They include controls for lighting and heating in 1.8 million non-domestic buildings as soon as possible. At present, fewer than 40% of buildings enjoy effective control of lighting and heating, and the call is for that figure to reach 90% or more. The urgent requirement is not just to install controls but also use them better.

Looking beyond 2020, technologies such as natural ventilation, biomass and triple glazing can increasingly be implemented. An important objective is to achieve the holistic operation of buildings — with services such as lighting, heating and ventilation working together.

Ensuring success after 2020 will require innovation to deliver more lower-cost options for carbon reduction and a supply chain that is capable of delivering genuinely low-carbon buildings.

While recognising that the technologies exist to achieve targets for reducing carbon emissions, the Carbon Trust report is primarily focused on policy. The perspectives it contains are based on in-depth interviews with some 70 players across the entire value chain of non-domestic buildings. The ‘success scenario’ analysis was carried out with Arup and based on a detailed model which predicts carbon emissions from non-domestic buildings under a range of different scenarios.

In helping to deliver long-term reductions in carbon emissions from non-domestic buildings, the report recognises the various barriers that combine within a complex industry to create what it calls a circle of inertia that makes it difficult to define the business case. The issues, which could be presented in any order, are as follows.

Funders, for example, could provide finance, but do not perceive a demand from occupiers.

Owners/developers that would prefer buildings which are more energy efficient can find that the funder will not provide finance and tenants do not ask for such buildings.

And while tenants might choose an energy-efficient building, they can find that there aren’t any — and that energy is, in any case, not a material cost of occupancy.

It is against that background that the report argues that a transformation is required — both in buildings and in the industry that delivers them.

The report concludes that Government can take a leadership role in delivering this transformation and that there is clear demand from within the industry for Government to clearly set the long-term direction for the industry. Because there are so many barriers to success, a clear case is perceived for Government intervention.

It is quite clear that non-domestic buildings have much to offer in helping to reduce the UK’s carbon emissions. However, without a renewed focus from Government and business, there is a high risk that it will be left behind other sectors in the UK’s collective journey to cut emissions by 80% by 2050.

On the plus side, if the non-domestic sector meets the challenge set out in this report, the end result will be better, more comfortable and more productive buildings that can play their role in the low-carbon economy of the future — in addition to a significant financial savings for business of £4.5 billion over the next decade alone.